In April 2023, a song called “Heart on My Sleeve” caused a worldwide sensation. The voices? Unmistakably Drake and The Weeknd. But the supposed dream duet was not an official release. No marketing stunt. No leak. Just fiction. An anonymous user calling themselves “ghostwriter977” had synthesized the voices of the two stars using artificial intelligence and released the track on TikTok. It was a viral shock moment that raised many questions about authorship, authenticity, and control.

But while some fear the loss of artistic integrity, others are consciously exploiting the new possibilities. Musician Holly Herndon, for example, has developed Holly+, a tool that synthetically replicates her voice and makes it available to third parties for creative reuse. In the visual arts, artificial intelligence is also giving rise to new forms of expression, as demonstrated by the music video for Washed Out’s The Hardest Part, produced by Paul Trillo with the help of Sora.

Hand in hand with these advances, debates are raging: Is AI a tool that opens up new creative possibilities for artists—or a technology that standardizes and dehumanizes our creativity? While some celebrate it as a source of inspiration and creative sparring partner, others warn of artistic uniformity. The “No to AI Art” movement, protests on platforms such as ArtStation, and ongoing lawsuits against providers such as Stability AI are evidence of growing resistance. In 2024, over 3,000 musicians, including ABBA and Radiohead, called for legal protection measures in an open letter.

But how can we ensure that AI does not simply reproduce existing music? What role do ethical issues play, for example in relation to copyright or bias in training data? What does originality mean when AI can generate images, music, or text in a matter of seconds? Australian musician Nick Cave was horrified when AI attempted to imitate his style. His verdict: “This song is bullshit!” Cave argued that, for him, art arises from human emotions – from pain, passion, and experience. AI can only simulate all of this, but never truly feel it.

In 2022, the image “Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial,” created with Midjourney, won an art prize—without the jury knowing that it was created by a machine. The outcry was immediate. Similarly, the children’s book “Alice and Sparkle,” whose AI-generated illustrations elicited not only admiration but also sharp criticism. Many fear that human creativity will be diluted by AI – or worse, replaced.

Mikey Shulman, CEO of music AI start-up Suno, recently made the provocative statement: “I think the majority of people don’t enjoy the majority of time they spend making music.” His solution: “Just prompt for a song.” Creativity becomes a click process – efficient, but disconnected from craftsmanship and emotional expression. Providers such as Udio are also pursuing this approach. Platforms such as Splice rely on AI to play a supporting role: not as a substitute for creative processes, but as a tool that inspires, expands, and accompanies artistic work.

The central question remains: What vision do we associate with AI in art? Should it be an inexpensive and efficient production tool for commercial graphics, stock music, and automated content? Or can it be a catalyst that takes our creativity to a new level and enriches artistic processes?

Ali Nikrang is a researcher at the Ars Electronica Futurelab and professor of AI and musical creation at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Munich. He is convinced that artificial intelligence must not take over and automate the creative process. Technology should challenge people and motivate them to discover new creative horizons: “Creativity does not arise from mere copying, but from the further development of ideas and the overcoming of familiar patterns.”

Inspiration or imitation?

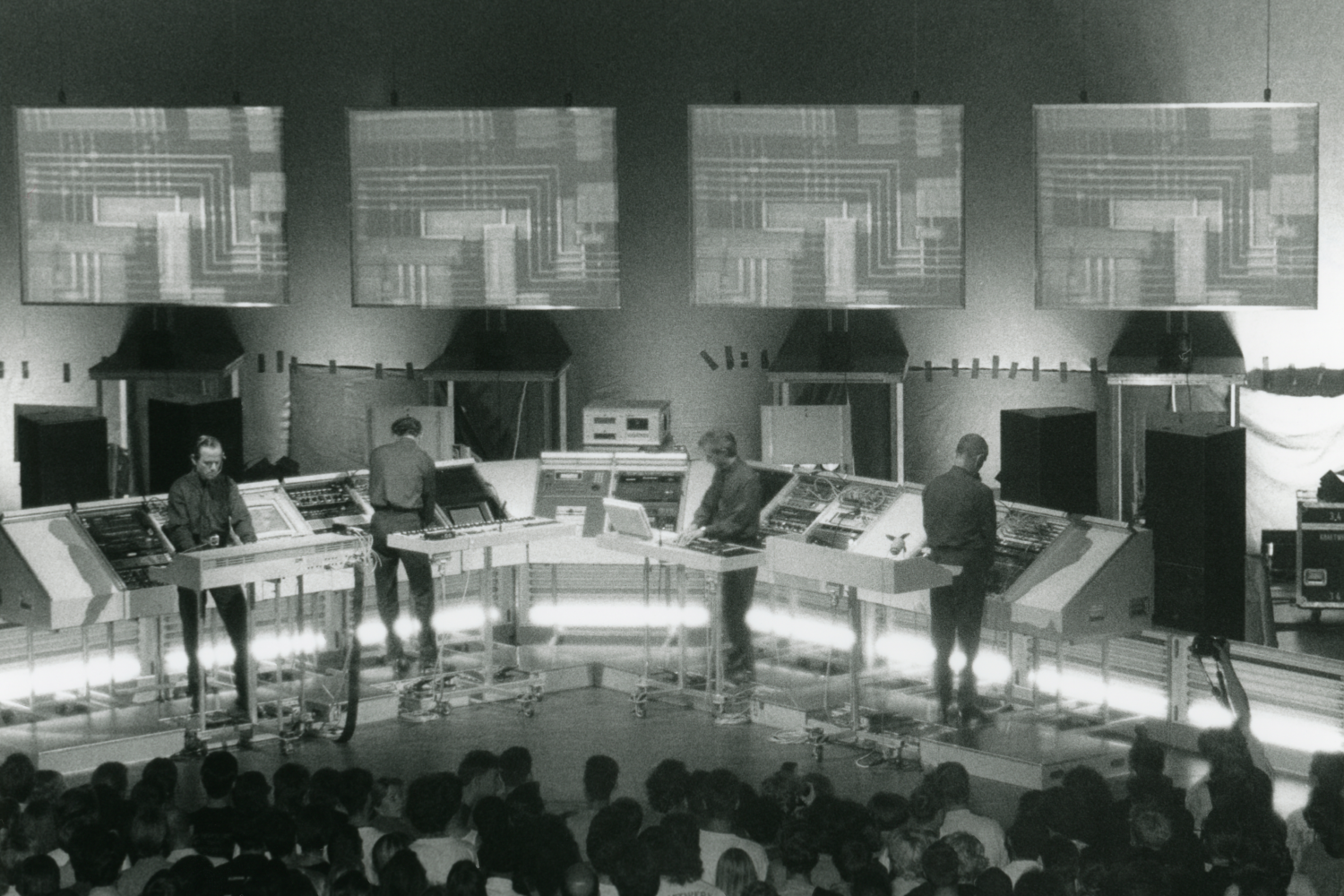

The history of music is closely linked to technological developments. New technologies have often opened up new musical possibilities and fundamentally changed artistic creative processes. In the 1960s and 1970s, music underwent a revolution: the synthesizer appeared on the scene. At the time, many considered it a foreign object, a cold machine that would never be able to replace the warmth of an orchestra. In the 1970s, synthesizers and sequencers enabled completely new methods of composition. Musicians such as Kraftwerk, Isao Tomita, and Wendy Carlos showed that these machines could not only imitate sounds, but also create entirely new sound aesthetics. Perhaps this also applies to AI?

In 1985, American composer David Cope was commissioned to compose an opera about the Navajo people living in Arizona and New Mexico. However, a prolonged bout of writer’s block prevented him from completing the commission. The closer the deadline drew, the harder it became for him to concentrate on composing. Colleagues at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) jokingly suggested that he let a computer help him compose the opera to overcome his block. He developed the program “Experiments in Music Intelligence” (EMI), which analyzed his earlier works and helped him generate compositional ideas. With the support of EMI, Cope was able to complete the opera “Cradle Falling,” which premiered in 1989. Critics were enthusiastic and celebrated the opera as “a modern masterpiece” – without knowing, of course, that a computer had been involved in its composition.

This early analysis program, a predecessor of today’s AI programs, shows what artificial intelligence can contribute to the creative process. “AI doesn’t have to be an imitation tool; it can definitely have an exploratory dimension,” explains Nikrang. “It’s not very appealing to artists if AI just imitates. It’s about developing new and individual concepts that go beyond mere reproduction.” The technology is trained with large data sets and generates suggestions that humans then pursue. Creativity emerges in a process of discovery, during which artists explore and specifically control the possibilities of AI in order to develop their individual concept.

“New technologies have always enabled new forms of artistic expression. I expect the same from AI,” says Ali Nikrang. And this is where it gets exciting: What soundscapes will AI open up for us in the future? What creative spaces will the technology open up for musicians, composers, and sound designers?

Despite many legitimate concerns, Ali Nikrang does not see AI as a threat: “AI is neither a simple brushstroke nor a self-sufficient artistic entity. It is a tool with its own peculiarities.” Just like painters experimenting with a new color, artists must learn to work with AI and explore its possibilities. “AI is not the end of art, but a new canvas. It does not provide ready-made answers, but rather a creative space that can produce completely different results depending on the intentions and visions of the artist.”

Will our perception of music change when machines start composing? Or is this just the next step in a long history of technical innovations that have always shaped the sound and understanding of music?

Artificial intelligence meets classical music

Ali Nikrang is exploring these questions as part of the “Waltz Symphony” project, a collaboration between Johann Strauss 2025 Vienna, the Ars Electronica Futurelab, and several music academies. The aim of the project is to find out how AI can be used in music composition without imitating existing works. Ali Nikrang is working with students and AI technologies he developed himself. “It’s not about AI simply imitating Johann Strauss. It’s about new, individual artistic concepts,” he emphasizes.

Students from the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, the Mozarteum Salzburg, the Zurich University of the Arts, and the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich are working with “Ricercar,” an AI system developed by Ali Nikrang that has now been specially trained with music by Johann Strauss. “It was exciting to see how the participants’ approaches developed,” says Ali Nikrang. ”Many of them were encountering AI for the first time, and it quickly became apparent that AI is not only a technical challenge, but also opens up new creative avenues.”

“Ricercar” is an interactive, AI-based music composition system that has been developed by Ali Nikrang at the Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz since 2019 and, since 2023, in parallel at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Munich. Unlike generative AI platforms such as Suno or Udio, which produce finished songs at the touch of a button, Ricercar is a support tool for musicians, especially in the field of classical music. The software does not compose completely automatically, but reacts dynamically to musical specifications and inspiration from users: for example, melodic, harmonic, or rhythmic structures, as well as parameters such as tempo, key, instrumentation, and articulation, which can be manipulated in a targeted manner. On this basis, Ricercar suggests compositional developments that can be accepted, modified, or rejected. The result is a dialogical process that requires musical know-how and aesthetic judgment. The name Ricercar is derived from the Italian “ricercare” – “to search” – and refers to a historical musical form of experimentation and exploration. This is precisely the principle underlying the system: the focus is not on quickly generating a finished result, but on jointly exploring musical ideas.

The future of creative collaboration

Will AI one day create art independently? Perhaps. The answer to this question depends less on the capabilities of the technology than on how we humans define “art.” And on the role we want to assign to AI.

AI can increase efficiency, but creative work is much more than productivity. A composer working with AI is not looking for the fastest solution, but for one that best captures their vision. “I think that AI will only remain interesting in the long term if humans remain in control as creators and AI does not degenerate into a purely automated, independent entity,” says Ali Nikrang. ”It should help artists create personal and individual works, rather than merely performing functional tasks.”

Ali Nikrang

Ali Nikrang is a multidisciplinary artist and researcher at the intersection of music and artificial intelligence. He works at the Ars Electronica Futurelab and is a professor of AI and musical creation at the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich. With a background in computer science and classical music, he develops AI-supported composition systems such as Ricercar and explores the creative potential of AI in music. His work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Venice Biennale Musica and the Misalignment Museum in San Francisco. He is also active as a jury member and in cultural policy committees.