Text: Martin Hieslmair

Photos: Claudia Schnugg, Jan Bernstein, Juliane Götz, Sebastian Neitsch

48.3096589° N latitude; 14.2838818° E longitude: Linz, Austria, February 23, 2016, 4 PM. This is the second consecutive day of deliberations by the 11-person international jury convened in the Ars Electronica Center to decide which of the 322 artists from 53 countries will get the extraordinary chance to travel to Chile for a Residency at the European Southern Observatory (ESO). This is now the third opportunity for artists to immerse themselves in a cutting-edge scientific field and take powerful inspiration for their artistic work home with them. And as in every art&science Residency, this South American trip is followed up by a sojourn at the Ars Electronica Futurelab. The results will premiere at the Ars Electronica Festival nd then be presented on the premises of the network’s other member organizations.

“Satellites” by Quadrature

“Voyager” by Quadrature

Quadrature, a German artists’ collective, succeeded in making the best impression on the jurors this time. After all, Jan Bernstein, Juliane Götz and Sebastian Neitsch not only bring to the table tremendous interest in and prior knowledge about the ESO’s locations in Chile; two of their previous projects—Voyager or Satellites—dealt with very similar topics. The three collaborators met at art school; in 2013, they founded a collective in which each individual contributes his/her own skills and focal-point topics. To learn more, read the interview with them on the Ars Electronica Blog.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

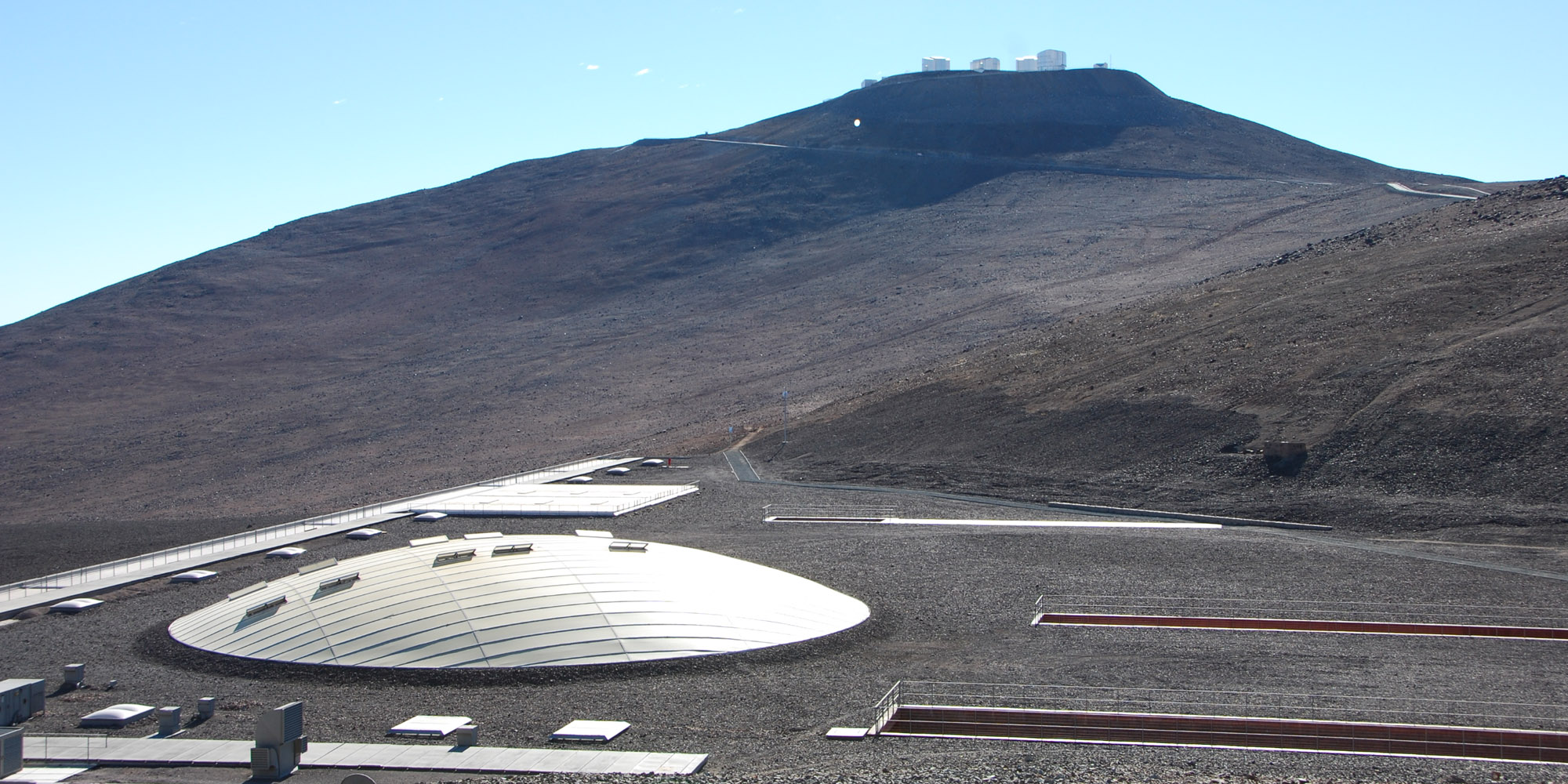

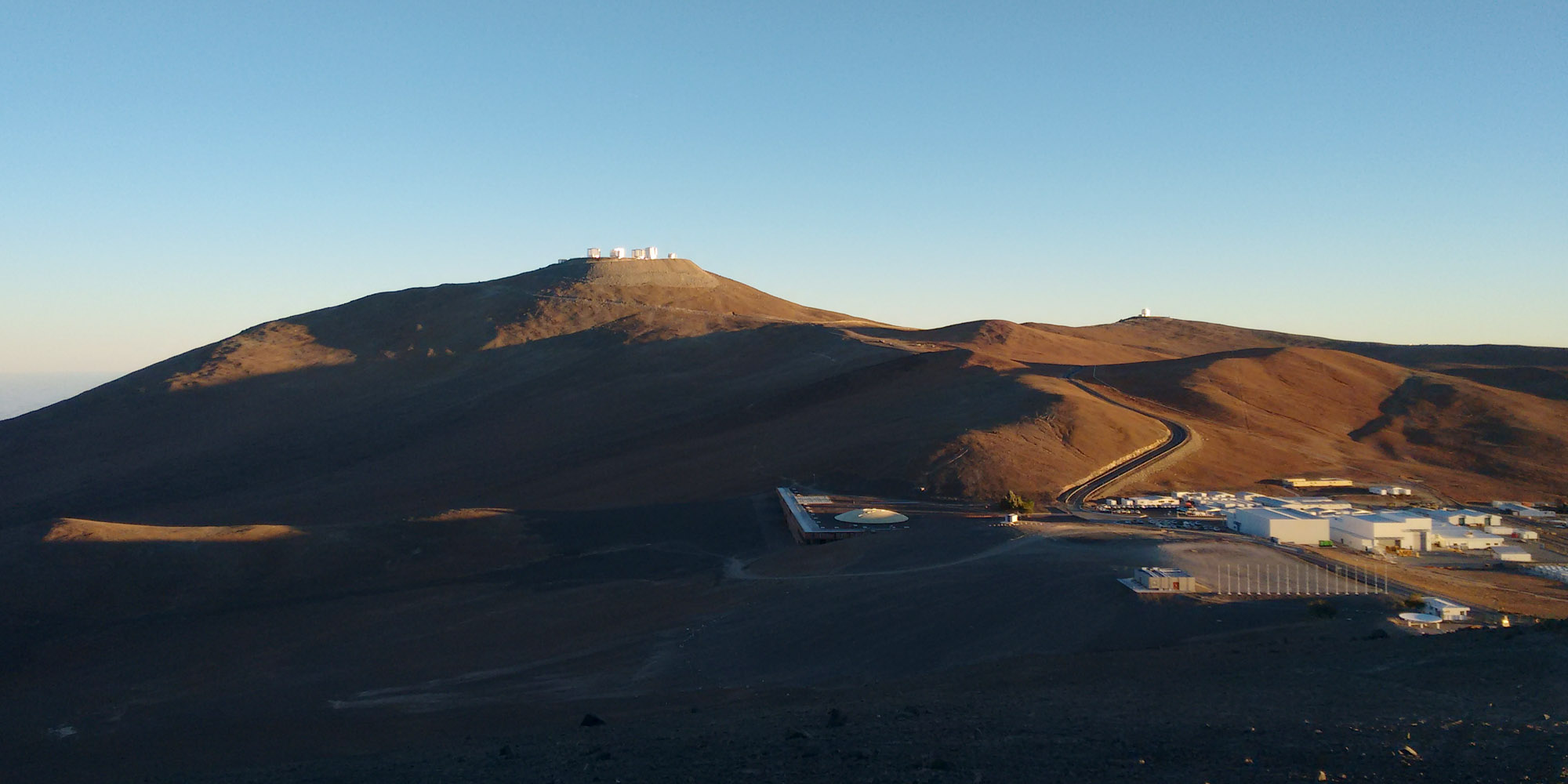

So now it’s time to set off for Chile and the ESO’s facilities. The excellent visibility from mountain peaks at an altitude of over 2,500 meters in South America’s Atacama Desert make this a superb location from which to get crystal-clear views into the depths of outer space—as long as the sun stays below the horizon and no clouds spoil the show. Founded in 1962, the ESO operates telescopes at multiple, unique observation sites where their astronomers have made several important discoveries. The next big infrastructure milestone comes in 2024, when the ESO’s European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) goes into operation. This story was making headlines in Chile just as we arrived with the artists.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

The first stop on our itinerary was the ESO’s headquarters in Santiago, where the artists had their first meeting with the organization’s scientists and astronomers.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

Seated on a circle of comfortable chairs in the ESO’s conference room, we enjoyed a pleasant chat that touched upon some organizational matters and elaborated on the respective scientists’ fields of research.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

The artists were also welcomed by Austrian Ambassador Dorothea Auer, German Cultural Attaché Barbara May, the director of the Goethe Institute, Volker Redder, and Arne Dettmann, editor-in-chief of the local German-Chilean newspaper.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

After this round of socializing with lots of new names and faces, things calmed down considerably as we headed into the huge expanses of the desert landscape. But on the access road to Cerro Paranal, a mountain about 12 kilometers from the Chilean coast, a sense of joyful anticipation took hold.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

The Paranal Observatory is perched at an altitude of about 2,600 meters above sea level; its telescopes are visible from afar. The next order of business: Visitor’s Passes, which are issued to the artists at the checkpoint.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

The accommodations for the scientists and staff personnel are about 200 meters away from the telescopes to prevent any pesky rays of artificial light from making a nuisance of themselves.

Credit: Juliane Götz

After a cup of Café de Paranal, we headed off on our initial inspection tour of the site.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

Four huge telescopes are ensconced in Paranal. They’re named Antu, Kueyen, Melipal and Yepun, and are so-called unit telescopes (UT1 to UT4) that make up the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). Thanks to numerous enhancements and adjustment, this array’s performance now surpasses that of the Hubble Space Telescope that’s orbiting the Earth. If you look closely, you see another unit—actually, more like a little gray garden shed—standing on the hill. That’s UT5, the telescope for visitors, since 2015.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

And just like at its bigger associates, the little UT5’s roof slides back to let you get a good look into the endless expanses of the cosmos.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

From the dormitory’s roof, you have a great view of the UT1-UT4, the next stop on the artists’ tour conducted by Fernando Comerón, the ESO’s man in Chile as well as the organization’s delegate on the art&science jury.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Before making their way to the telescopes, the crew had to move a couple of boulders that were blocking the path.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

This big boy had a bit part in “Quantum of Solace,” the 2008 James Bond film featuring scenes shot in Paranal.

Credit: Sebstian Neitsch

Quadrature arrives at the VLT platform; satisfied expressions in the first selfie at the site.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

The three were particularly taken with UT4. Besides its sophisticated optics, this unit features several built-in lasers that can produce an artificial point of light in the upper atmosphere, a Laser Guide Star (LGS) used in astronomical adaptive optics to correct atmospheric distortion of light.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

It’s kind of a pain in the neck to wear but, at some point, you just might be glad you had it on: the official ESO hard hat.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Fernando Comerón personally explained to the three artists how the VLT works, how the giant telescope can rotate, what calibrations are necessary, and the functions of the reflectors and lasers.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

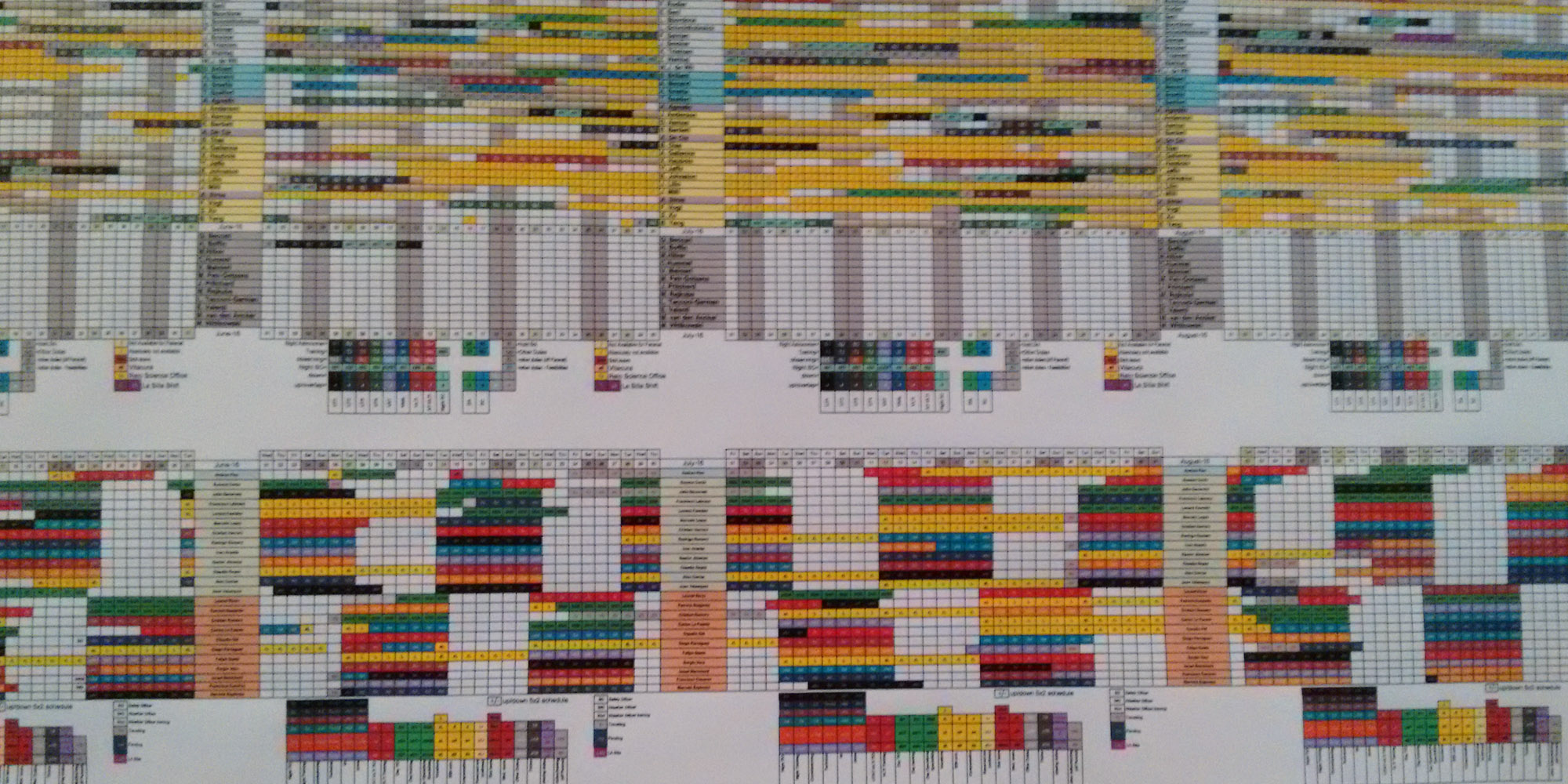

In the control room, the safety helmets are red and blue all of a sudden. And the important role that colors play in scientists’ information flow can readily be seen on the wall charts.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

Fernando Comerón is totally convinced that art and science inspire one another. He went into detail about this in an in-depth interview about the ESO’s activities we published on the Ars Electronica Blog:

“It is very refreshing for us to have these new perspectives from somebody who comes from a world that has nothing to do with the world of the visiting astronomers. Artists are having a fresh look to the observatory as a place not of high-tech, not of scientific discovery and not of technical jargon but as an inspiring place for something that is very different from the scope of the visiting astronomers.”

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

An exciting day comes to a colorful conclusion. As the sun sets into the Pacific Ocean, this workplace comes alive. Data is best gathered when its pitch-black out.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

The next stop on the tour of Paranal is the ESO’s coating area, where the reflectors used in the telescopes are recoated with aluminum.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Since the reflector’s reflective coating deteriorates over time—due to oxidation or wear and tear—these sensitive elements have to be recoated every few years.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

The coating equipment weighs over 100 tons and, like the artists, comes from Germany. It was delivered in the 1990s by ship via the Danube, the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal, Antwerp, across the Atlantic Ocean and through the Panama Canal to the Chilean port of Antofagasta.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Instrument Inside.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

At some locations in Paranal, shoes need to be covered up too for the sake of the delicate devices.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

In the metal workshop where technicians build and repair the ESO’s instruments, Jan Bernstein feels right at home. The trained metalworker had a blast scrutinizing the machinery and equipment.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

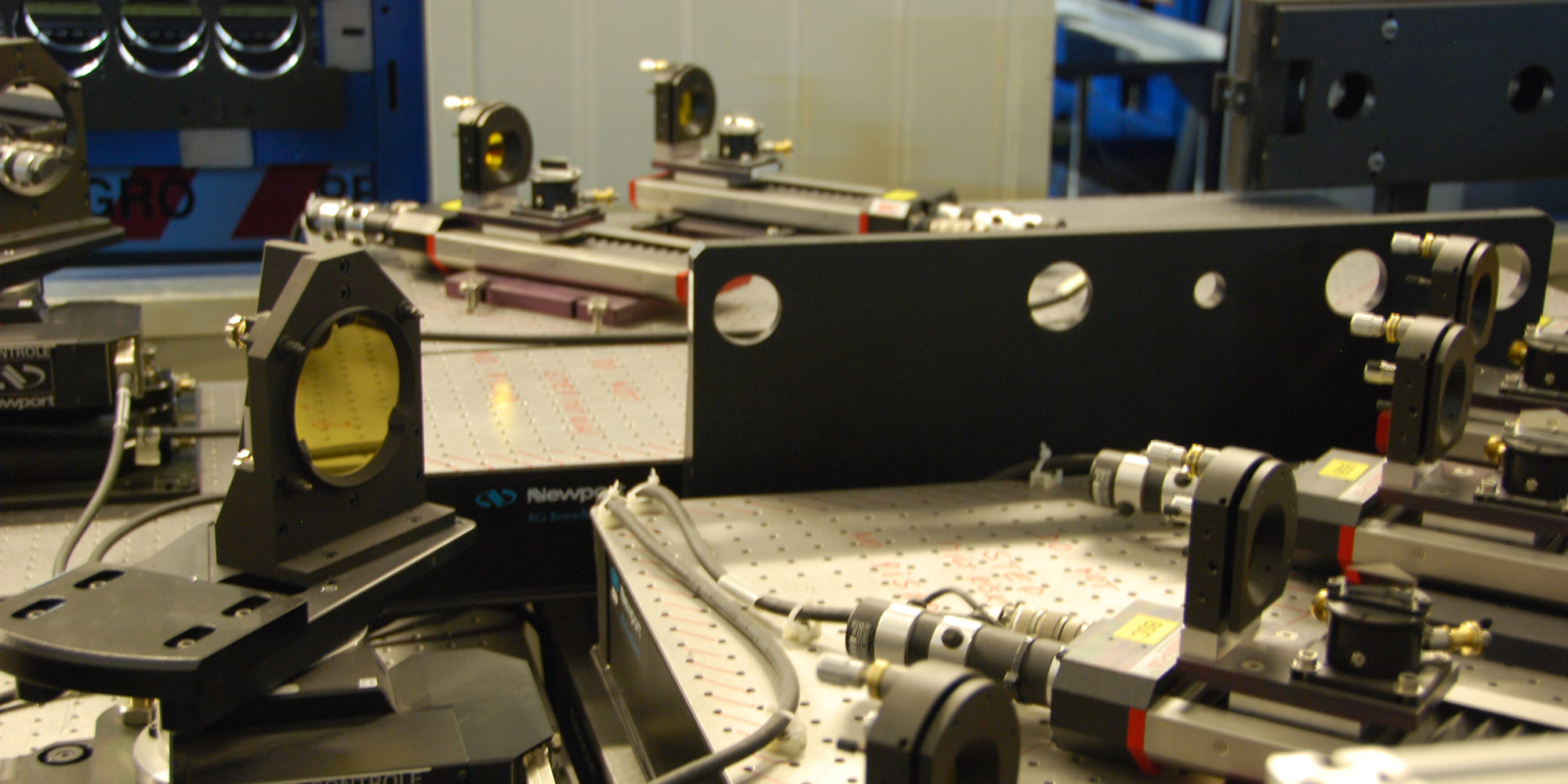

Then it’s on to the VLT’s interferometry tunnel. Interferometry? OK … conventional ground-based telescopes are much too small to be able to see things like the surface structures of one of our neighboring stars; doing so would take a reflector 1.5 kilometers in diameter! But the main reflector of each of the four telescopes here in Paranal has a diameter of only 8.2 meters. Larger reflectors would not only be incredibly expensive; useful ones couldn’t even be produced in our planet’s gravitational field since they’d immediately be deformed by their own weight.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

That’s where the tunnel comes into play. Thanks to interferometry, several reflectors can be interconnected to produce the same views of the universe you would get if a much larger reflector were deployed. Thus, for this very large “virtual” telescope, a tunnel of this kind is nothing more than a differential delay line for the waves being fed in from the four individual telescopes.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Meanwhile, back in the inhospitable habitat of the Atacama Desert, Jan Bernstein’s on a solo stroll across this extraordinarily arid stretch of our Blue Planet’s surface.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

It’s a good time to turn our thoughts back to larger issues. Jan Bernstein said in the interview:

“Outer space as a location is very real and at the same time intangible. Its size and endlessness make it an incredibly abstract, almost unreal idea, the dimensions and contents of which often exceed our powers of imagination. These boundaries of the possible and the feasible, of the intellect and of knowledge are what interest us most.”

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

This place is paradise for photographers too. After all, the sunsets are heavenly, and the cloud and mountain formations are absolutely out of this world! There are aesthetic images in every direction you look.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Not far from Paranal’s extant telescopes, a parcel has been staked off where a structure of a very different sort is to be built. Here’s where earthmovers will soon begin construction of the European Extremely Large Telescope (EELT) featuring a main reflector 39 meters in diameter. The world’s largest optical telescope is scheduled to go into operation in 2024. That extremely small figure dancing on the horizon is Sebastian Neitsch.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

We’re still in Paranal, even if it looks like Mars. Night returns. If we weren’t in such a hurry, it would have been nice to camp out here for a few weeks.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

How did the artists come to be fascinated by the cosmos? Sebastian Neitsch gave a very simple explanation in his Ars Electronica Blog interview:

“We grew up with stories and images of our universe, both real-life accounts and utopian ones. Rockets, time travel, space stations, life on Mars, aliens … Scientists aren’t the only ones for whom the cosmos and space exploration provide a virtually inexhaustible source of inspiration.”

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Several painted stones adorned the roadside along our route to the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) in the vicinity of San Pedro.

Credit: Sebastian Neitsch

If the car had broken down, we could have taken a bus.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

It would have been a pretty long hike through the Valle de La Luna.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

At APEX, a large radio telescope with a reflector 12 meters in diameter, we got a tour of the facility from scientist Carlos De Breuck.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Francisco Montenegro, an astronomer and director of the scientific group, then accompanied us up to APEX’s roof, where you have a terrific view of the antennas of the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) that we’ll get to in a moment. The good visual contact is also important because it guarantees efficient radio transmission to ALMA of the data captured at APEX.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Time: late May; Temp: -7° Celsius. And it’s windy to boot. Scientist Michael Dumke, perfectly attired for the occasion, demonstrates to his knowledge-hungry guests from Europe how fast a telescope can actually pivot.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

One glimpse into the instrument chamber speaks more than a thousand words.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

But a thousand words are nowhere near enough to explain all the details of the technological procedures that take place here.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Having requested access to ALMA, the world’s largest radio telescope, we’re waiting for the health check-up. Situated at 5,000 meters above sea level, not everyone has the constitution for such an outing. This is where humankind is endeavoring to find out how stars and planets are born. To achieve this, several partners from Europe, the USA, Asia and South America have formed an alliance.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

In his blog interview, Jan Bernstein already mentioned that he was especially looking forward to seeing ALMA:

“A visit to the ALMA facility, which is apparently quite an elaborate undertaking, has really gotten us curious—precisely because of the great difficulty of reaching this place. The thin air up there, the mandatory fitness check, the long journey to even get there—we won’t soon be taking another trip so close to outer space.”

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Fernando Comerón escorted us through the control room and, in his congenial manner, gave an elaborate explanation of the various bandwidths and their interplay.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Whoever seeks more in-depth information can simply refer to the wall helpfully outfitted with a Front End Cryostat poster. An explanation of what in the world that is surely goes beyond the scope of this presentation. Anyway, Sebastian Neitsch saved it to his cell phone for future reference.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Thankfully, scientist Armin Silber was on hand. He conducted our exclusive tour through ALMA and elaborated on all further details.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Out among the patches of snow in the sandy desert landscape are no fewer than 66 antennas that can be shifted about into all sorts of complex arrays.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

What does it feel like to take a trip like this? This is what Juliane Götz told the Ars Electronica Blog prior to her Residency:

“Actually, we feel a bit like explorers ourselves, like we’re trailblazers who are being permitted to penetrate a remote, inaccessible region to obtain insights into another world. We know the ESO locations from photos, we’re aware that they exist. But now, to actually have access to this sort of “scientific colony,” this crazy high-end technology, and to experience this secluded, isolated part of the world—this is a highly auspicious prospect.”

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

And here they are: the high-end- & the low-loader, transporters Otto and Lore. They’re the ones that move the 66 antennas from Point A to Point B.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Each configuration of the antenna is for a particular research objective. Is high-definition the highest priority, or is it the largest possible expanse of sky? A couple of times a year, Otto and Lore help reposition the beautiful, snow-white antennas.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

A week and a half in Chile just flew by. Here, the Quadrature crew—Jan Bernstein, Juliane Götz and Sebastian Neitsch—enjoys a pleasant dip in one of the nearby hot springs. And we express our gratitude to all those ESO staff members and partners who made it possible for us and the artists to experience this impressive expedition!

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

A few weeks later, back in Europe—at the ESO’s headquarters in Garching, Germany, to be precise—we and the artists once again receive a gracious reception from Fernando Comerón and his staff.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

There are still a few open questions. In response, scientist Gerardo Avila uses Fernando Comerón’s access cards to explain how another mirror system works.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

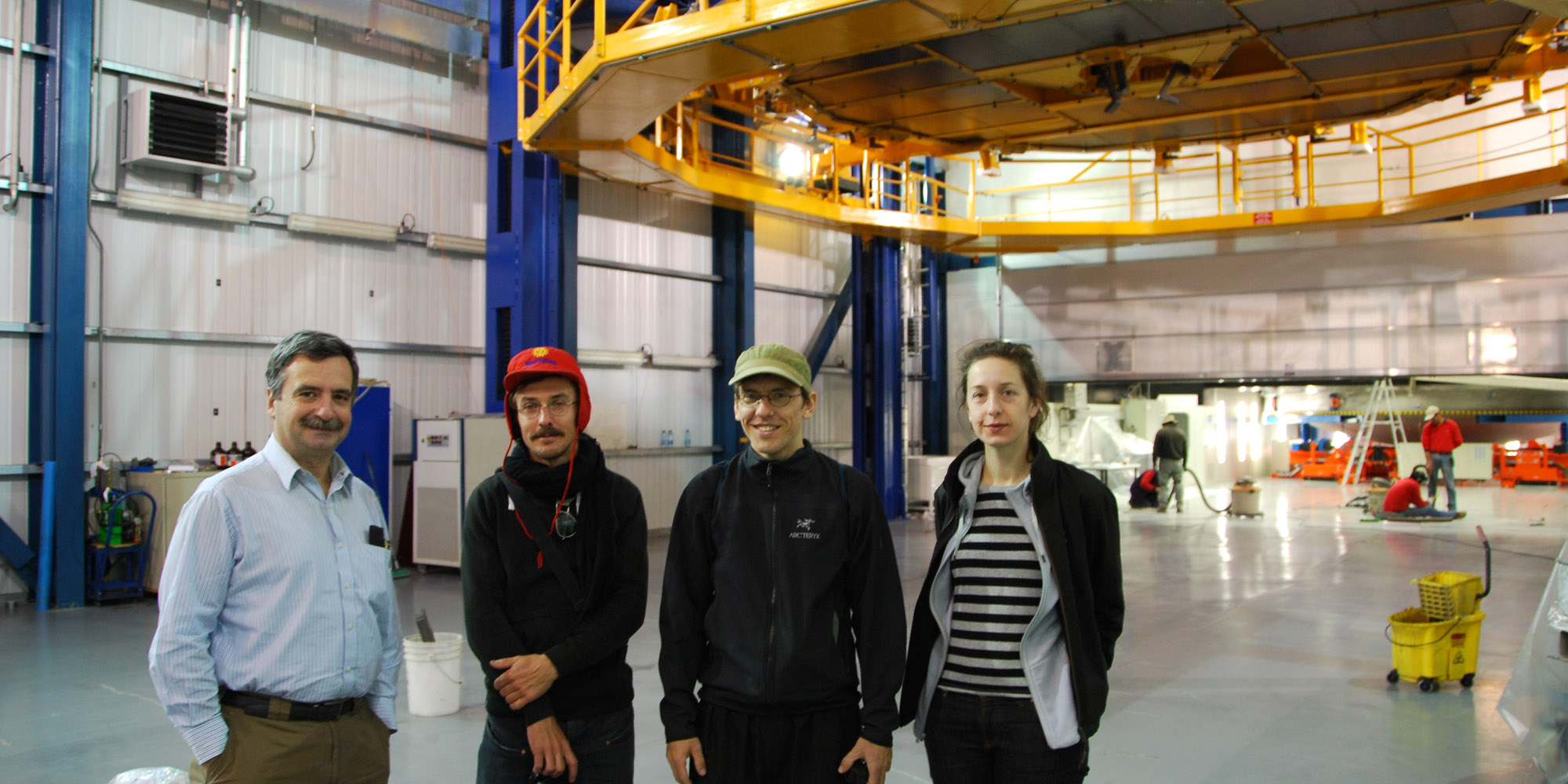

Here in Garching in the vicinity of Munich, the ESO Supernova visitors’ center is now under construction. Time for hard hats again. Lars Lindberg Christensen leads the tour of the site.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Carlos Guirao shows Jan Bernstein a spectroscope that measures the properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

Juliane Götz, for her part, is more interested in the CCD camera that the ESO uses to transfer their images to “film.” Javier Reyes serves as Infotrainer.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

And what’s Sebastian Neitsch doing? He’s paying attention, of course, as Javier Reyes goes into detail about laser beams and the technology behind them.

Credit: Claudia Schnugg

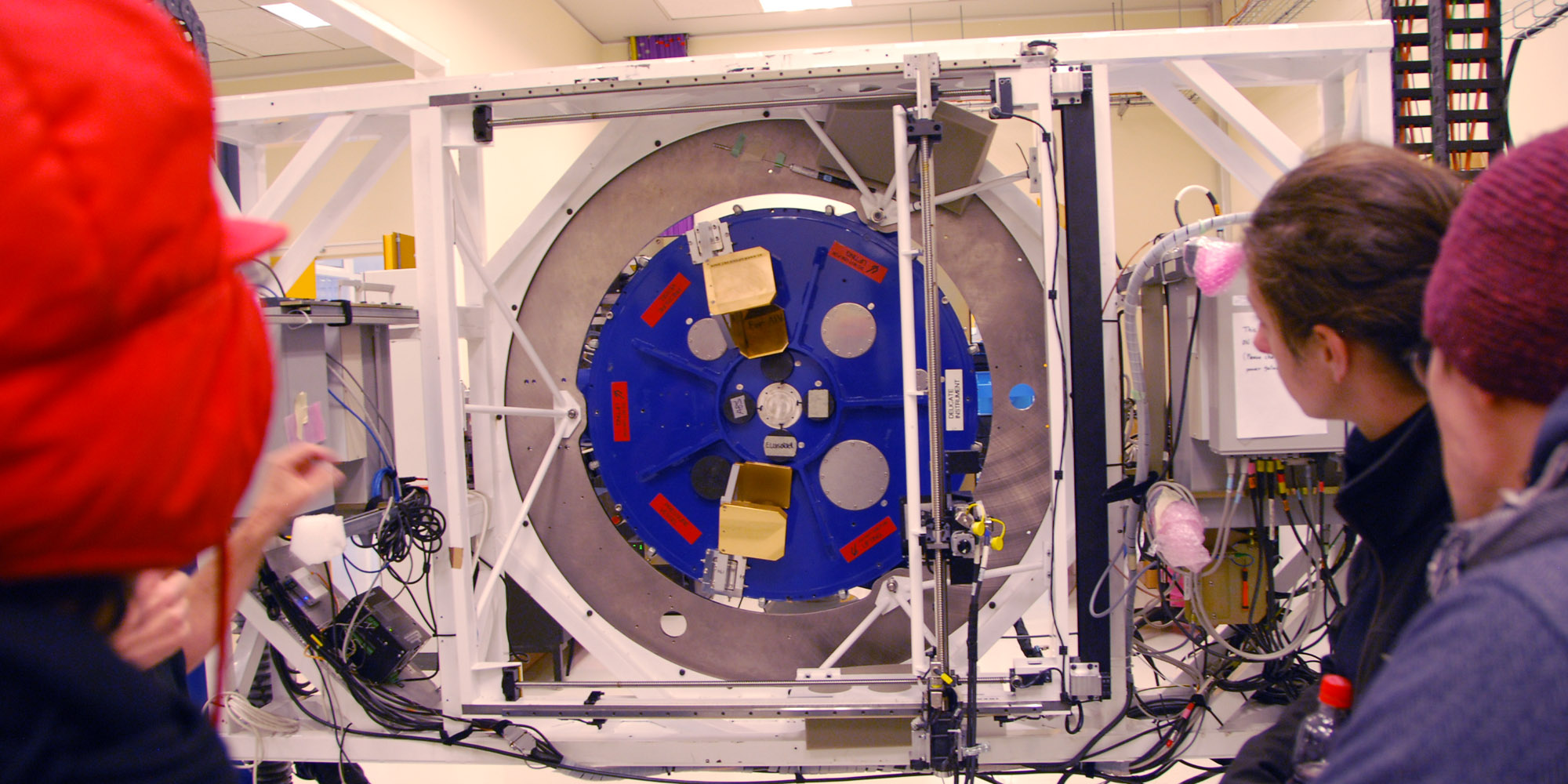

Shortly before the end of this leg of their protracted journey, the artists dropped in on the Integration Lab, where Samuel Leveque described tests being performed there.

Credit: Samuel Leveque

From left to right: Fernando Comerón (ESO Chile), Claudia Schnugg (Ars Electronica Futurelab), Jan Bernstein (Quadrature), Juliane Götz (Quadrature) and Sebastian Neitsch (Quadrature).

And do the artists like what they’ve experienced thus far? We asked them to comment briefly:

“They’re wide awake at night, and regenerate in the daytime. The huge white telescopes are incessantly at work in an effort to eliminate the last disruptive terrestrial influences. As technically superior creatures, they perform an endless dance of calibration and observation. There is no cause for alarm … but there probably will be …”

That last line is an automated announcement that’s repeated every 5-10 minutes in one of the ESO’s control rooms in Chile by way of confirmation that everything’s OK in all the telescopes outside. A nice metaphor for the endless calibration process, this line actually comes from a popular ‘90s TV show, “Pinky and the Brain.”

The next stop on Quadrature’s itinerary is the Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz, where, September 8-12, 2016 at the Ars Electronica Festival RADICAL ATOMS and the alchemists of our time, you’ll be able to see for yourself what the artists’ collective has made out of this Residency. We’re looking forward to seeing you there!