We’re standing before Mount Rushmore, the heads of four presidents looming above us. They’ve been chiseled right into a rock face, hugely larger-than-life and recognizable from miles away. But we’re moving in for an extreme close-up—so close that you can make out minute details of the structures. But wait a minute! How is that even possible? This is normally off-limits.

Not so in MasterWorks, a virtual reality (VR) application developed by a non-profit organization named CyArk. They’ve used laser scanning, photogrammetry and a tremendous amount of drone footage to digitally reconstruct four World Cultural Heritage sites and make it very convenient for the general public to experience them up close. We did a skype interview with Elizabeth Lee, vice president of California-based CyArk, to find out more about the application, which visitors to the Ars Electronica Center can now get hands-on experience using.

Could you tell me a little bit about what you and your team at CyArk do?

Elizabeth Lee: Sure! CyArk is a non-profit organization. We’ve been around since 2003, with the mission to digitally record, archive, and share the world’s cultural heritage. We do this in order to capture these amazing places that tell us about our past and help connect us to those around us, with the hope of inspiring wonder and curiosity in the people around us.

We focus our work in three primary areas. One is around supporting recovery efforts through our archive. By collecting this data, we are making sure we have a very accurate record of the sites, so that if anything catastrophic happens, it could be used to aid in recovery efforts. We also work in support of active conservation and management today. This means getting better drawings, plans, and detailed information to site managers, archaeologists, and architects that help them do their jobs. Finally, we also use the data we record to help promote the discovery of these places, like with MasterWorks. We are using VR to bring people face to face with these incredible sites.

Credit: CyArk

MasterWorks is your first public VR installation… How did this come about?

Elizabeth Lee: We were always really interested in the potential for Virtual Reality, just because it works quite well with our data in its native form. We’re capturing very high resolution 3D environments, so it makes perfect sense for then actually viewing them sort of life-size in VR. About a year ago, we started a conversation with Oculus and their education group, and they were quite interested in seeing types of content that could be developed in support of education and life-long learning. We worked with Oculus and another third-party developer called FarBridge to create the MasterWorks experience, to select three different sites that people could visit virtually, and also learn from experts who work at these sites.

Credit: CyArk

So one of the functions of MasterWorks is education, but it’s not the only one. You also collect for professionals who work at the sites. How does VR play into this?

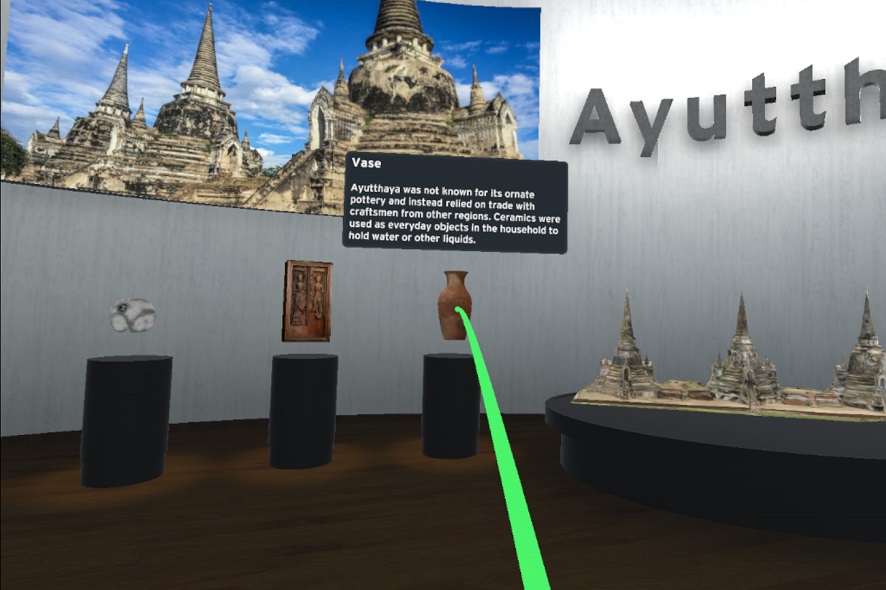

Elizabeth Lee: I think the underlying data that we collect actually supports both of those functions. To take an example of one of the sites in MasterWorks, the site Ayutthaya in Thailand: That project came about because there was major flooding there back in 2011. There are these beautiful, bell-shaped chedis, and one them is settling quite a bit. There’s a subsidence at the site and no good baseline record before the flood to know how much that monument was leaning before and how much the flood actually impacted the site. They called on us to help do the documentation, so that they would have those baseline-records.

We collected laserscans and photogrammetry and drone images to create a 3D model, and for the conservators and the architects we produced a set of drawings, sections and elevations of site that actually have all the measurements so they can monitor the site. We used that same 3D model to bring it into MasterWorks. The dataset is being used by the Thai fine arts department to make decisions about the site, and at the same time, when you are in the VR experience, you can hear members from the fine arts department talking about the site, its importance and some of the challenges that it faces.

With all the data you are collecting, aren’t you actually gathering more than you would need for a VR application?

Elizabeth Lee: Yes! We have much higher resolution than the current headsets can support. So our team has to do quite a bit of data processing. We start with a very high resolution model and use the highest resolution to create drawings for the experts on site. Then we have target specifications that we are trying to hit for the release devices, the Oculus Rift and the Samsung Gear VR. This means we have two different types of specification for the total number of polygons and the total number of textures that could be supported on those devices. The hope is, of course, that as the VR technology gets better, we have the data to be able to support higher resolution experiences! But it also meets our needs today, because on the conservation sites they sometimes need drawings in a much higher resolution than you could show with VR to make decisions.

Credit: CyArk

Where do you see the benefits of VR for education, cultural heritage, and art mediation?

Elizabeth Lee: For us, what’s been incredible about releasing MasterWorks is that while still early for VR, there are museums that are setting it up and enable people to come in and have this experience, even though and they may never get a chance to really travel to some of these places. The sites are prohibited or really remote, so it’s an incredible opportunity to expand people’s horizon and to teach them about some of these places.

In one of the other sites that is in MasterWorks, Mesa Verde National Park, you get to walk around an area called Balcony House. This place is open to the public, but it’s a very difficult site to access: You have to climb a 30-foot ladder and there are small passageways that you have to squeeze through. Not all of the visitors that come to the park have the opportunity to visit Balcony House, but through VR, there is an opportunity to set something up in the visitor’s center that would give people the opportunity to experience the site, even if they are not physically able to go there. I think in terms of access, there’s huge potential.

One of the things that was really important for us is bringing in the voice of the expert. Within all the experiences, you are learning from people that work at those sites today. This provides the sites with a completely different perspective. You get to hear from the archeologists who have worked there for maybe 30 years, who really understand the site and can share some of its stories with you.

How do you see VR developing in the future?

Elizabeth Lee: It is still early, but I think we are going to see a lot more applications on the mobile side. The experiences that you can have in the Oculus Rift with a laptop or a desktop computer is really fantastic, because of the quality, but it is cumbersome and therefore limiting as a result. So as more of the technologies move towards mobile-type platforms and untethered experiences, VR is going to get a lot more accessible. Google has done so much with their Google Cardboard, a very low-cost cardboard viewer for smartphones, and I think that this started to demonstrate the potential. Obviously, the quality of that experience is much lower, but I think as the mobile technology improves, we are going to see, let’s say, classrooms, that have 30 mobile-type headsets in the room for all their students, and they can take them on real virtual field trips.

What’s to consider if we want to responsibly integrate VR into our lives?

Elizabeth Lee: One of the things that is important for us and for our vision is to responsibly represent the sites. For us, it is about using the real data and showing the site as it looks today. From another perspective than the cultural heritage field, it could be very easy to use VR and make beautiful reconstructions of the sites which may not have the same research behind it and may not be this accurate, but I think there is some danger in presenting the information in this way. Especially when the experience is so immersive! Still, anything that opens up access and gets people excited about these sites and our shared history is positive.

Lastly, we are of course all curious – what is next for CyArk?

Elizabeth Lee: We actually just took our first step towards a real open archive! We launched an open heritage initiative with Google, where we released full-sourced data for 25 sites. This is something we are particularly excited about, as well as about the applications that people can use the data with. The datasets are all available under a non-commercial license. And then, our hope is to produce another VR experience that builds on the success of MasterWorks and takes people to new, exciting places.

Elizabeth Lee serves as Vice President for CyArk, an international non-profit organization with the mission to capture, archive and enable virtual access to the world’s cultural heritage. Her expertise includes developing international partnerships in support of technology driven solutions for cultural heritage protection, education, and tourism. Originally trained as an archaeologist with excavation experience in Turkey and Hungary, Elizabeth has been applying 3D reality capture technologies to the cultural field for over a decade. She has completed over 100 projects working with dozens of cultural ministries, the United Nationals Educational Cultural and Scientific Organization (UNESCO), and top technology companies including Microsoft, Autodesk, Seagate, and Iron Mountain.

MasterWorks, a VR installation by Elizabeth Lee and her crew at CyArk, has been installed in the Ars Electronica Center’s VRLab. Visitors are invited to take it for a test drive! Click here for more info about the VRLab.

To learn more about Ars Electronica, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al., subscribe to our newsletter, and check us out online at https://ars.electronica.art/news/en/.