Times are challenging, even for us who have lived in a state of peace for almost 80 years. It is hard to imagine what it is like to suddenly wake up under war conditions. To no longer be able to publicly express one’s own opinion as an artist for fear of being politically persecuted. To have to flee because you’ve raised your voice.

We at Ars Electronica are convinced that these are precisely the times “when we need art as a space in which contradictions can be possible without immediately excluding one position or another,” says Gerfried Stocker, artistic director Ars Electronica. “It’s a minefield, of course, but the times when you could draw very clear divisions between good and evil are, at least currently, times gone.” At the same time, art and curation wants and needs to confront and address these very contradictions that war and political persecution raise. “That is absolutely important, even if someone then perhaps sees it as an imposition, that her/his position is also critically commented on. To perceive and present contradictions does not mean to accept or even to affirm the positions that are opposed to each other. Not to fade out the contradictions, but to dissect them, to dismantle them, to expose them without immediately judging them, is I think much more important.”

Under these difficult conditions and with a look ahead to the current State of the ART(ist) Call, with an extended submission deadline until July 3, which expressly seeks to support politically persecuted artists-not only but especially from Ukraine-we spoke with Martin Honzik, CCO of Ars Electronica, about the challenges involved in the curation process, how one can confront these contradictions, and what one’s own limitations are and always will be confronted with in the process.

What role do artists or art in general play in political events, in a war? Even among artists there are different political tendencies, not all of them automatically stand up for human rights or for freedom of expression…

Martin Honzik: That’s a difficult question. What is the role of art in times of war? The role of art in wartime should not be overestimated in principle, nor can it be a generalized one. I myself, or rather my generation, have experienced nothing that comes close to this, apart from the stories of our parents’ and grandparents’ generations and the war in the former Yugoslavia, which came very close. History has shown time and again that of course artists have also gone to war as soldiers – voluntarily or conscripted – as in Ukraine. And there have also been times when war has been idealized, glorified, and advocated through the lens of art.

“Art is not warlike, but neither is it peaceful.”

It is being produced and imagined by people of all possible backgrounds and attitudes, and in turn read and interpreted individually by others. The experience we have gained so far in the current conflict is a mirror of the one just described. For example, we have many connections and relationships with the Russian media art scene, which is a constant and important part of the whole scene. There is fear and desperation, shame towards the Russian position and loyalty towards Ukraine. We know of some who are trying to help Ukrainians directly in Russia, of some who are trying to continue a normal life, and also of some who are trying to leave the country or have already done so. However, it is noticeable that all those who remain in Russia are more and more cautious with open criticism, or do not dare to express open criticism anymore.

We are already very excited about the submissions of the call, which, by the way, does not exclude Russian artists, on the contrary! However, it is also clear that we will not address war supporters with this project and will also not allow propagandistic art in the call.

We have decided to cooperate only with individual artists or individual collectives from Russia. We have terminated or suspended any form of institutional cooperation until further notice.

Let’s talk about the status quo, about how difficult it is to make a call not only in these times but virtually about a war event. How uninvolved can and should you be, how do you position yourself and how do you deal with propaganda?

Martin Honzik: It is basically a complicated situation to make a call of this nature and orientation, if you are in an external position yourself. It is simply beyond our imagination what war means, causes and changes and what is the right way to deal with traumatized people, or whether there is a way to deal with it at all in a general and correct way. And, it is also not foreseeable how this possibility, which we offer, will be accepted and perceived at all or whether it addresses those whom we want to address.

The only controllable thing in this situation is to act on one’s own intention, to influence one’s own attitude and activities and to try to take the role of a bridge builder with art and culture. We will most certainly be enriched by the submissions and the direct contacts that will result, but most certainly also by the many mistakes that we ourselves will make and the misunderstandings that we will cause and encounter.

Let’s talk about another current example. At ESERO Austria, the “European Space Education Resource Office”, which has been run by Ars Electronica in cooperation between the European Space Agency (ESA) and national partners in Austria since 2016, we keep presenting Art & Space projects. Here, too, we encounter precisely this curatorial problem, can you explain that briefly?

Martin Honzik: Exactly, for the occasion we would have liked to present a Ukrainian group in the series of these Art & Space projects. With Noosphere we also found a nice project. Now the group is selling NFTs and wants to donate the proceeds to the Ukrainian army. How does a cultural institution deal with the paradoxical situation of suddenly being indirectly involved in financing a war? We will support this project, by the way, and we will find ourselves in similar situations, all of which must be considered and negotiated anew for themselves. This shows the complex present in which we live, how difficult it is to evaluate it and to conclude the right thing from it, and it also shows, above all, that war overrides everything that is culturally common and established, and that the assessable boundaries between good and evil dissolve.

As Gerfried Stocker already said when introducing our festival theme, art can offer a space where contradiction can be possible without being mutually exclusive. A space that neutrally accepts contradictoriness, does not fade it out, but brings it into focus, dissects it, disassembles it and exposes it, without judging and without evaluating. Art and culture, which is also inherently contradictory, can thus represent an offer to society, a social laboratory in which reality can be simulated and in which one can meet again under different circumstances and thereby test oneself.

What exactly does a curation look like then, how can it adapt to such changing conditions? And how can I display this in the exhibition context?

Martin Honzik: The selection process for an art award usually follows the logic of a mature jury of experts and a catalog of criteria that can be relatively clearly declared and formulated in the respective genre of art. We are conducting this call for the first time and therefore do not yet know the nature of the submitted works and how they differ or resemble each other. An evaluation will only be possible once we have been able to get a picture of all the submissions. We will certainly find a way to make content and form assessable and comparable. However, it will certainly also be important to understand from and in which situation the submission or the work of art has arisen. Due to the global questioning of the call, it will not be exclusively artists who have created their art from war or crisis areas, but most likely artists will also submit who basically have something to say about the topic, but do not necessarily come from crisis areas. Making these two fundamentally different perspectives comparable will certainly be part of the challenge for the jury.

It will also be important, as already mentioned, to filter out submissions with a propagandistic background in advance. Once this process is done, it will be a matter of providing the selected works with space and communication. In this specific case, the works will be exhibited and made accessible in a virtual space. This will serve to make the works accessible beyond the rather short festival period from September 7 to 11, and also to remind us of the basic vision of the Internet – a place that can democratically serve people across national borders to be able to express themselves openly and safely there. Incidentally, compared to the previous two years, this will be the only program item at this year’s festival that takes place exclusively online.

What do artists get out of participating in the Call, what is our offer to them?

Martin Honzik: We strive for the most sustainable support possible instead of a one-time distribution of profits. That means we provide an honorarium, we take care of the transportation or the journey and the accommodation to the festival. We want to offer the entrants the possibility of a continuation of their artistic path, their career, to have them present internationally. This includes the participation at the festival, which acts as a presentation stage, the accessibility of the virtual exhibition spaces beyond the festival as well as the cooperation with the ministry to continue to ensure the travel of the submitting and selected artists.

In conclusion, this part of the program will be a central part of the festival. The virtual spaces will be accessible from everywhere and this access will be quite low-threshold. At the festival, the spaces will be presented through the 4dBox – a holographic installation. Around this presentation there will be online and on-site discussion formats.

Can you perhaps give a few examples of the kind of projects that are being sought?

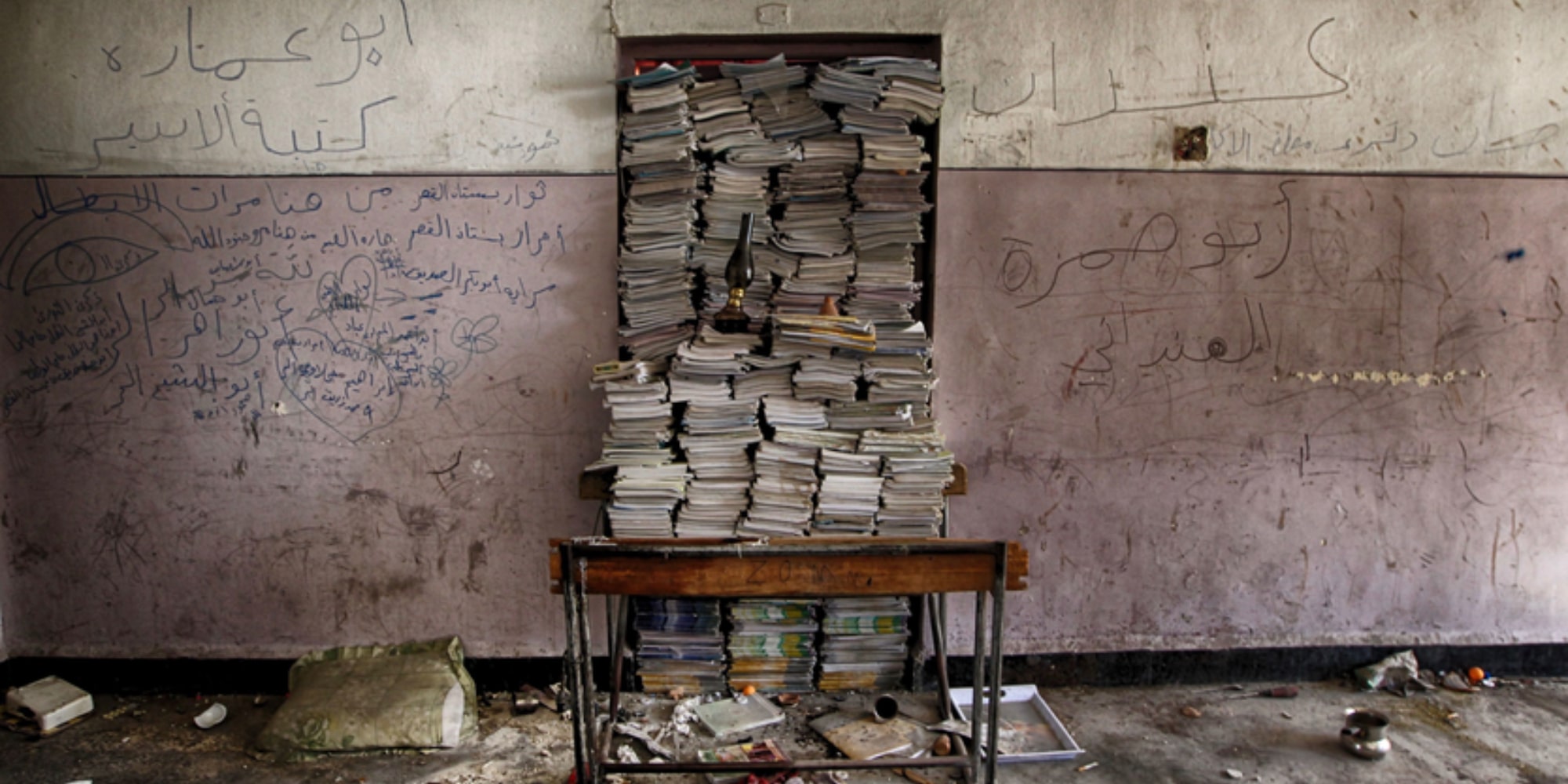

Martin Honzik: Basically, there are many works from the Prix Ars Electronica pool that have already dealt with the subject of war. But what we can expect remains exciting. There’s no doubt that our usual framework-media art-will be massively expanded. All forms of artistic expression are welcome. This can range from street art to literature to the classical art disciplines.

The evaluation criteria, however, will not be those of the Prix Ars Electronica. It can be assumed that extreme situations like this one will produce extreme modes of expression and alternative forms of art. There will be a difference between someone reflecting and expressing something from a safe situation and someone trying to express themselves directly from a war zone, from a crisis area.

Martin Honzik is an artist, CCO of Ars Electronica Linz, and Managing Director of the Ars Electronica’s Festival, Prix and Export. He studied visual experimental design at Linz Art University (graduated in 2001) and completed the master’s program in culture & media management at the University of Linz and ICCM Salzburg (graduated in 2003). Besides being independent Artist in several art projects, he joined the staff of the Ars Electronica Future Lab as a researcher, in 2001, where, until 2005, his responsibilities included exhibition design, art in architecture, interface design, event design and project management. Since 2006, Martin Honzik has been Managing Director of the Ars Electronica Festival, the Prix Ars Electronica, the Exhibitions in the Ars Electronica Center and Ars Electronica Export. He has been curating a considerable amount of international Exhibitions in the context of Art, Science and Technology. Additionally, he became CCO (Chief-Curatorial-Officer) of Ars Electronica Linz in 2021.

The State of the ART(ist) Call runs through July 3, 2022 (extended deadline). Details about the submission, the exhibition and the cooperation can be found here. The selected works will then be presented at theArs Electronica Festival 2022.