How artists started to explore the social dimension of the electronic space.

Long before the Internet began to attract widespread attention in the form of the WWW and before a young generation of artists began to critically examine the structures, peculiarities, and future possibilities of this new medium under the term “Net Art,” telecommunications art projects began to take place (from the late 1970s onwards) dealing with global networking. From the outset, Ars Electronica was a venue for this pioneering artistic work.

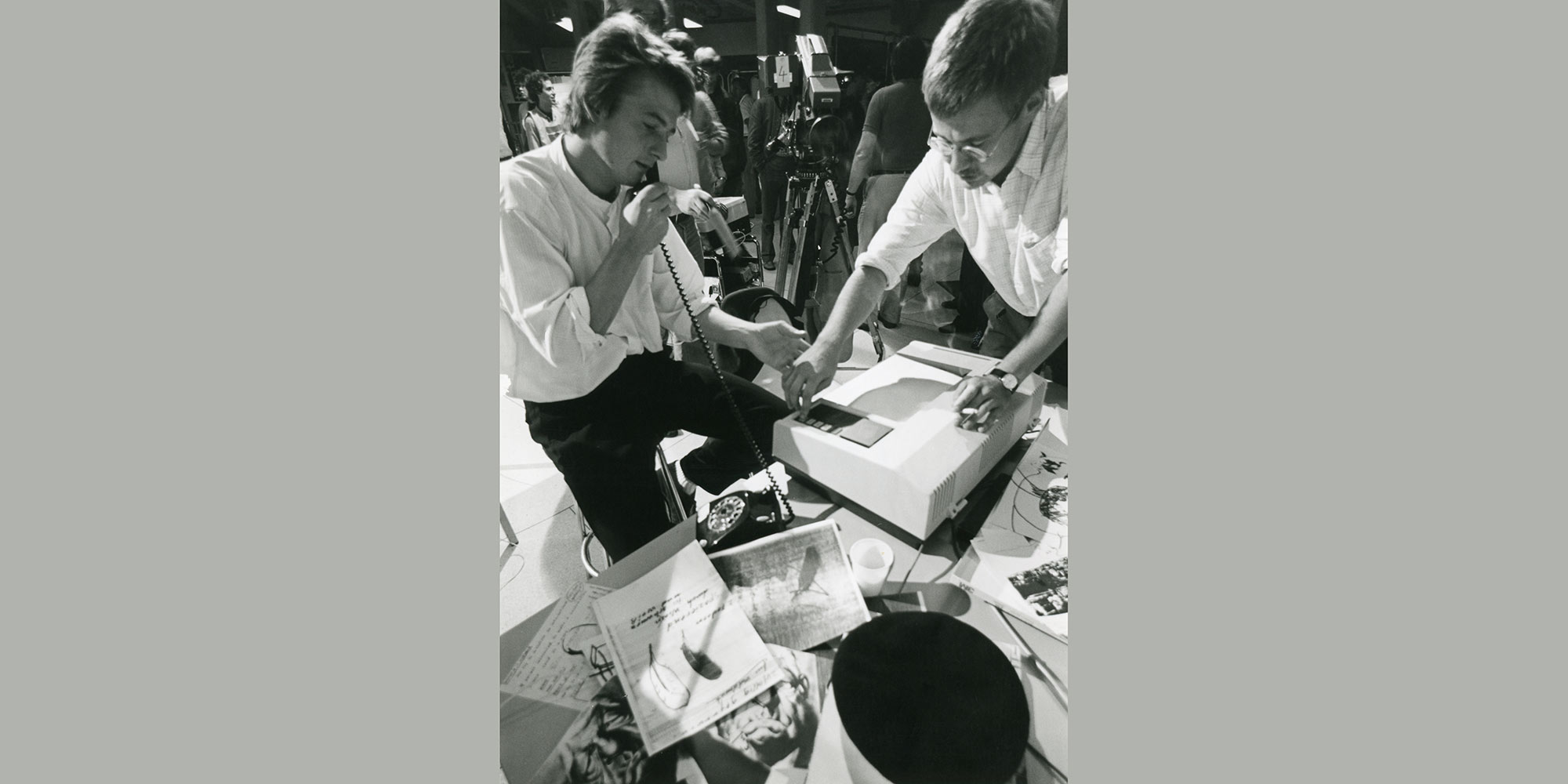

One of the now legendary early projects took place at Ars Electronica in 1982: “The World in 24 Hours” organized by Canadian/Austrian artist Robert Adrian, together with a large number of international partners. For an entire day and at every hour, the ORF regional studio in Upper Austria produced telecommunicative situations online, each with a different location in the world, using all available possibilities. The aim was not to create works of art, nor was it to create performative situations, but to be connected, to establish electronic space as a place of encounter and exchange – in other words, to try out exactly what is now our everyday life with social media.

Using documentary material from the archives of Ars Electronica, Ö1-Kunstradio and Outerspace by Doug Jarvis, the exhibition attempts to trace the peculiarities of these early projects.

Another section of the exhibition is devoted to the visionary media projects from the 1980s by Van Gogh TV, the Linzer Stadtwerkstatt-TV, Radio Subcom, and the many projects that were created in cooperation with the Ö1 art radio station in the 1990s.

A separate part of the exhibition is dedicated to physical telepresence. It very quickly became an interesting field of artistic exploration, since the aim was to combine the virtuality of digital space with our physical reality, to extend the human-computer interface beyond the distance of the telematic connection, and to be able to become active and directly affect both realities at the same time. Documentary materials from “Telegarden” (1996), from “Bump,” the telekinetic wooden bridge between Linz and Budapest from 1999, or from the projects Hiroshi Ishii presented at the festival since 1997, prove the fascination of this collaboration between art and technology.

Another exhibition area will also be dedicated to the beginnings of “Net-Art.” It presents exemplary projects and protagonists such as Etoy, Radio TNC, Ricardo Dominguez’ *Digital Zapatismo* as well as the many winners of the relevant Prix categories for Net-Art and later for Digital Communities.

What makes all these projects so exemplary from today’s point of view is that artists did not approach the new technical reality as a tool with which they produce their art(s), but recognized that the real impact of digital networking lies in the fact that it creates a social space; and they saw it as their task to examine the cultural and social effects of this development.

On behalf of society, artists claim their place with these projects, claim their participation in the emerging electronic space, which has been above all – unfortunately – a monopolized commercial space, both then and now.

The fact that we still today, to extent perhaps greater than 40 years ago, lack a real public sphere in the digital networks, instead tolerating an almost feudalistic arrangement within the latifundia of the digital landlords, whose arbitrary rules we are subjected to, is probably the gravest failure so far of our path into the digital age.