Ars Electronica is the future, cultural heritage is the past. Both tell of disruptive interrelationships at the intersection of art, technology and society. In Deep Space 8K, they enter into a unique symbiosis.

Art and cultural treasures are unique and everlasting. Whether paintings, sculptures, plays, literature, films, installations or architecture – it is the creativity, virtuosity and vision of their creators that are expressed in them and still amaze us centuries, even millennia later. But it is also what these works symbolise. Just as layers of rock tell us about the climate, fauna and flora of geological eras long past, cultural heritage traces the improbable course of the development of our civilisation. It tells of images of the world and people, power relations and conflicts, of winners and losers, disruptive technologies and business models, of ancient longings, great dreams and very everyday worries.

‘Art and cultural treasures not only reflect the political, religious, technological or artistic facets of their time. They also reveal the canon of values of the society that declares and appreciates them as such,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘What is considered “cultural heritage”, where, how and by whom it should be preserved and what stories it tells are always answered differently. This has less to do with a changing assessment of artistic quality and more to do with what a work stands for: we are much more likely to label art that symbolises a time, ideology or society that we see as positive with the label “cultural heritage” than art that was created in eras or by cultures that we reject.’ It is therefore no coincidence that cultural heritage often falls victim to destruction when it comes to building a new society: ‘In the midst of symbols of a past to be left behind, it is difficult to create a new beginning.’

Art, technology, society

Michaela Wimplinger maintains contacts with museums, art and cultural institutions, collections, galleries, start-ups, foundations and embassies around the world. Since 2017, she has been responsible for special projects and collaborations at Ars Electronica and manages special formats, including conferences, exhibition contributions and presentations in Deep Space. Together with colleagues from all areas of the company, she is increasingly working to bring digitised art and cultural treasures to the Ars Electronica Center in Linz. They are made accessible to the general public here as unique immersive experiences. ‘We are making cultural heritage one of our storylines about how art, technology and society influence each other. Art and cultural treasures become lenses through which we can view and reflect on our past, present and future.’

Portal into other worlds

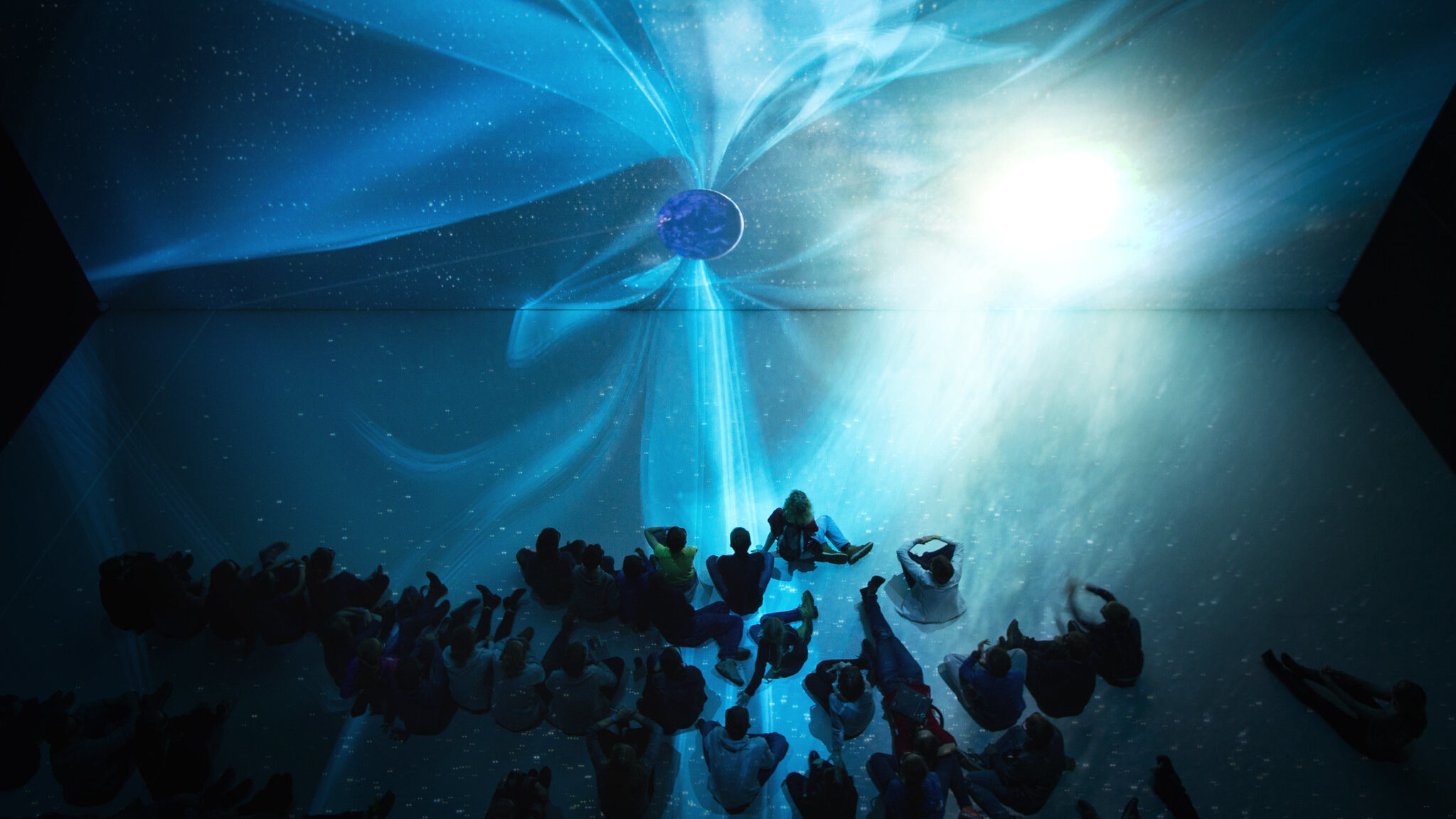

Where and how this happens is unique and the result of decades of development. ‘Linz was the European Capital of Culture in 2009 and the Ars Electronica Center was expanded to 8500 square metres. Part of the architectural tender was a room that was to be used exclusively for huge high-resolution projections. The Ars Electronica Futurelab was responsible for the technical development of this “Deep Space”. The new Ars Electronica Center opened on 1 January 2009 and the “Deep Space” with its 16 x 9 metre 4K wall and floor projections went into operation. ‘The visitors were perplexed.’

The most popular at the time was a 3D visualisation of the entire known universe. ‘”uniview” was an eye-opener,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘Just as you were busy with the usual everyday problems, the next moment you were lost in this beautiful universe with its myriad of sparkling planets, stars and galaxies. You felt so tiny and insignificant, but also so privileged to be able to exist on this one planet in the middle of this huge something.’ For the first time, ‘Deep Space’ had unfolded its immersive potential and the question arose as to whether cultural heritage could also become a unique experience here.

From catalogues to immersive spaces

The digitisation of art and cultural treasures was nothing new at the time. The first efforts to catalogue and digitise museum and library collections had already been made in the 1960s. With the spread of the internet and technological advances in scanning and digital image processing, these endeavours gained increasing momentum. 1996 saw the launch of the ‘Internet Archive’, the first digital archive for books, websites and other cultural assets, and in 2002 the ‘Open Archival Information System Reference Model’ was certified as an ISO standard. In 2004, Google initiated its ‘Books Library Project’ to digitise millions of books and in 2008, the European Union’s digital library ‘Europeana’ was launched. ‘After Standford University had already created very precise three-dimensional models of Michelangelo’s sculptures in 1999, things got really exciting in the 2000s, especially due to advances in 3D scanning, photogrammetry and virtual reality,’ recalls Michaela Wimplinger. ‘More and more three-dimensional digital models were created that turned legendary artefacts and sites from human history into immersive experiences. In the form of “Deep Space”, Ars Electronica then had a completely new infrastructure to offer for precisely such projects.’

Cultural heritage in ‘Deep Space’ for the first time

‘Deep Space’ quickly became a crowd-puller and a coveted stage for artists from all over the world. Gigapixel images, data visualisations, interactive games, concerts and performances explored the potential of the immersive prototype time and time again. Cultural heritage was also included in the programme which kicked off in 2011 with a point cloud created by CyArk of the ancient Mayan city of Tikal in present-day Guatemala. In 2013, the Austrian painter Hermann Nietsch presented a selection of his famous Schüttbilder, and in 2014, gigapixel images of art and cultural treasures such as Cellini’s ‘Saliera’ (Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna), the ‘Ebstorf World Map’ destroyed in 1943, Ingres’ “La Grande Odalisque” (Louvre) and Cranach’s “Venus in a Landscape” (Louvre) were shown.

8K

In 2015, ‘Deep Space’ became ‘Deep Space 8K’. ‘The Ars Electronica Futurelab team gave the room a major technical upgrade. Instead of 4K resolution, eight brand-new Christie projectors now project images in 8K resolution at a frequency of 120 frames per second. The brightness of the images was also increased from 12,000 to 30,000 ANSI lumens,’ explains Michaela Wimplinger. ‘To promote the immersive potential of “Deep Space 8K”, we also needed new content.’

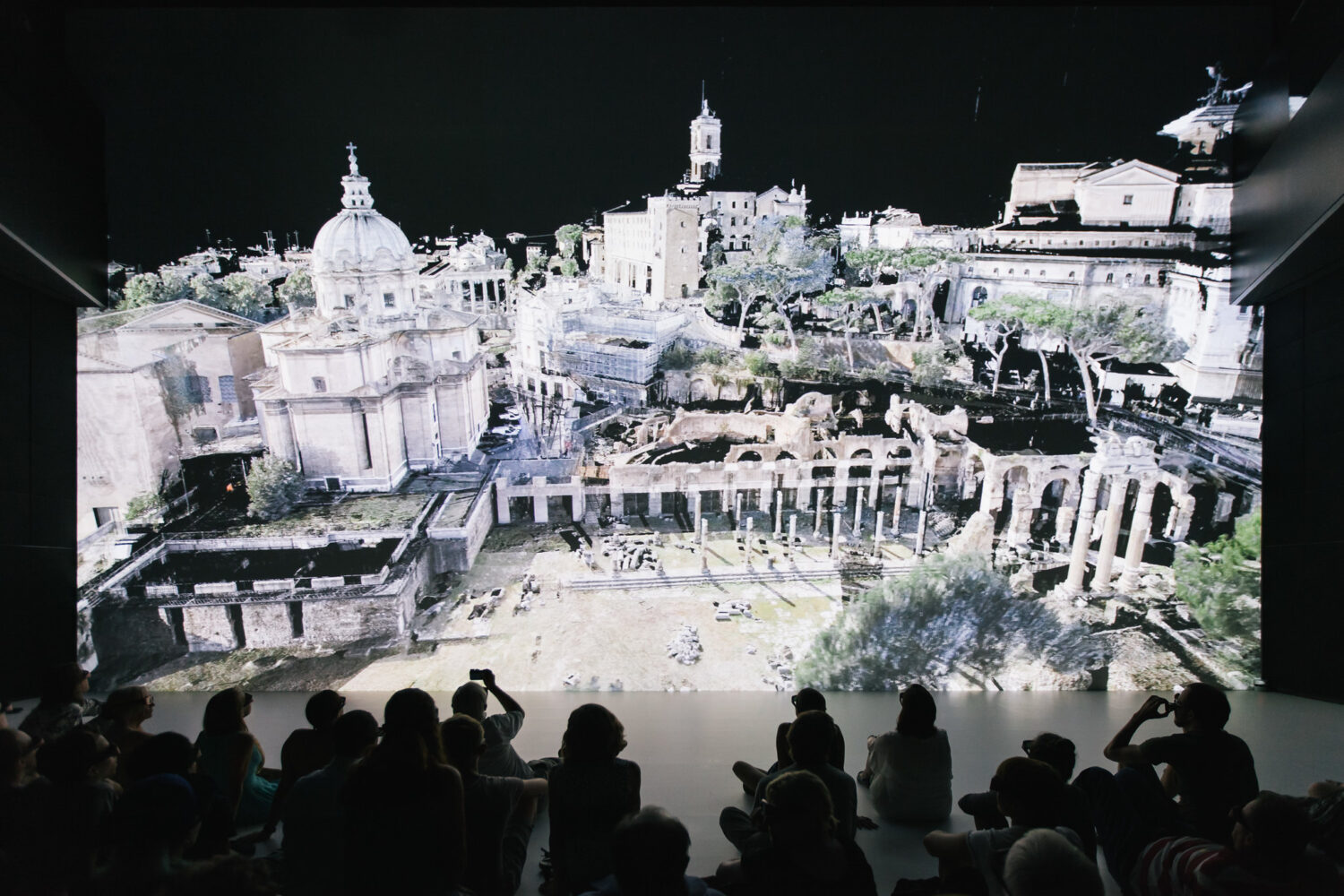

Better than television – a walk in ancient Rome

‘As luck would have it, the BBC was producing a 60-minute documentary on ancient Rome and commissioned the ScanLAB team to use laser scans to visualise the ancient city structures beneath modern Rome. The preparation of the data for “Deep Space 8K” met with great interest, and the Ars Electronica Futurelab set to work. When it became possible to walk through ancient Rome in deep space, it wasn’t just the visitors who were amazed – the people from the BBC were really impressed, too,’ says Michaela Wimplinger with a smile.

More cultural heritage

The following year, visitors to ‘Deep Space’ were able to experience a virtual reconstruction of the Linz synagogue. ‘Like so many Jewish places of worship, the synagogue in Linz was set on fire and destroyed by the Nazis during the Night of Broken Glass on 9 and 10 November 1938. This virtual reconstruction, which the Ars Electronica Futurelab team adapted for “Deep Space”, was created as part of a diploma thesis at the Vienna University of Technology.’

Gigapixel images of the famous Venus of Willendorf, a 29,500-year-old Venus figurine from the Gravettian period, were also featured in ‘Deep Space’ in 2016. The figurine, which is only 11 cm tall, is one of the most important examples of the oldest known works of art.

‘I found it all incredibly inspiring and wanted to help give more people access to art and cultural treasures. I wanted to make cultural heritage the focus of my work,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. At the beginning of 2017, she sought dialogue with the management of Ars Electronica and won them over. ‘I was really pleased,’ she recalls. ‘We had a really great package to start with: the Ars Electronica Futurelab would continue to develop “Deep Space” and prepare data sets, while the Ars Electronica Center would contribute its decades of experience in storytelling. Then there was the Ars Electronica Festival, which brought experts from all over the world to Linz every year, and the Prix Ars Electronica, through which we reached artists who found completely new staging possibilities in “Deep Space”. All we needed were partners with high-calibre content and art-historical expertise, and sponsors to finance the project.’

„Sharing Heritage“ – Pieter Bruegel in Deep Space 8K

2018 was the European Year of Cultural Heritage. ‘The theme chosen by the European Commission was “Sharing Heritage”, which was the perfect starting point for us,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. In collaboration with the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna and the General Delegation of Flanders of the Belgian Embassy, she managed to bring gigapixel images of paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder to Linz. ‘The images were presented by Geert Van der Snickt from the University of Antwerp, Frederik Temmermans from the Free University of Brussels and Manfred Sellink, Director General of the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp,‘ recalls Michaela Wimplinger. ‘It was a real experience to see Pieter Bruegel’s works in “Deep Space 8K” and to hear experts talk about his life. The great feedback we received at the time made me incredibly happy – and spurred me on.’

In Cheops pyramid

In 2019, visitors to the Ars Electronica Centre were able to view gigapixel images of the “Tabula Peutingeriana” (Austrian National Library) and Egon Schiele’s painting “Trude Engel” (Lentos Kunstmuseum) in Deep Space. There was also a further collaboration with the BBC and ScanLab. ‘For a documentary on the Cheops Pyramid, a high-resolution, three-dimensional model of the ancient wonder was created and processed for Deep Space by the Ars Electronica Futurelab as part of the EU-sponsored research project “Immersify“. Visitors were able to move around the virtual pyramid and freely control their field of vision. The visitors were enthusiastic and we were motivated to tackle the next projects.’

Pandemic

In 2020, everything turned upside down. ‘On 30 January, the World Health Organisation declared an international health emergency due to the rapid spread of the coronavirus and before we knew it, we were in the middle of the pandemic,’ recalls Michaela Wimplinger. ‘Lockdowns, quarantine, working from home, short-time working, Zoom calls – working conditions were extremely difficult and all our projects were suddenly uncertain.’ In contrast to many other art and cultural institutions that cancelled their events, Ars Electronica decided to continue and hold both the exhibitions and the festival, but in a different way. ‘Within a very short space of time, we organised exhibition tours, workshops, concerts and deep space presentations online or in hybrid form. It was clear to me that our cultural heritage activities would not be paused either.’

Raffael and Jan van Eyck

It was this pandemic-ridden 2020, of all years, that marked the 500th anniversary of the death of the genius Raphael. ‘The Italian company “Magister Art”, which specialises in digital heritage, had therefore developed a new project entitled “Magister Raffaello”, in which the “Entombment of Christ” from the Galleria Borghese as well as the “Madonna with the Goldfinch” and the “Self-Portrait” from the Uffizi were first digitised as gigapixel images and then used to create a video,’ explains Michaela Wimplinger. ‘Magister Raffaello’ was supported by the Italian Cultural Institute in Vienna.

The second highlight of the year was a project with the Museum of Bruges, the General Delegation of Flanders and the Belgian Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage and Art in Flanders. ‘In April, the altar designed by Jan van Eyck in Sint Baafs Cathedral in Ghent was reopened after a long period of restoration and the whole of Flanders declared 2020 a year of celebrations centred on the exceptional Flemish artist,’ explains Michaela Wimplinger. ‘We managed to obtain high-resolution images of this world-famous altarpiece and show them in Deep Space. Till-Holger Borchert, the director of the museum in Bruges, was on hand for the presentation and explained not only the paintings, but also van Eyck’s creative environment and techniques.’

Guernica

‘Without realising it, it was tragically a very fitting decision to show Picasso’s “Guernica” in September 2021,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. Just a few months later, in February 2022, the conflict between Ukraine and Russia escalated and the Russian invasion began. ‘At the time, we were much more concerned with the division in our society between those in favour of vaccination and those against it, which is why we wanted to show a work that upheld democracy. Mabel Tapia, Deputy Director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Madrid, and Olga Sevillano, Head of Digital Projects at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Madrid, were guests in Linz at the time. Together they presented Picasso’s ‘Guernica’.’ The project was supported by the Spanish Embassy in Vienna.

Deep Space Evolution

In March 2022, the Deep Space 8K itself took centre stage. ‘The Ars Electronica Futurelab team had been working for months to raise the technical performance of the prototype projection room to a new level,’ explains Michaela Wimplinger. The projection room was now equipped with four laser projectors that could display a much larger colour space but consumed around 30 percent less power. Because they didn’t get as hot, they didn’t need to be cooled as much and were therefore much quieter. All seven workstations on which the ‘Deep Space 8K’ ran were also completely renewed and the computing power was increased by around 200 per cent. A significant increase in performance was also achieved with the graphics cards – instead of four, only two were needed per computer, which in turn reduced their power consumption by 40 per cent. ‘Under the motto “Deep Space Evolution”, we then invited people to the media event and opening at the end of March and were delighted to see lots of shining eyes and open mouths.’

Women then and now

Shortly afterwards, an exciting artistic encounter was on the programme with ‘Merlic meets Klimt’. ‘Our theme was the changing image of women,’ explains Michaela Wimplinger. ‘With Franz Smola, we had a renowned Klimt specialist as our guest, who used the example of high-resolution Klimt paintings to show how women were conceived as idealised in the 19th century. We contrasted this with Rebecca Merlic, a young artist from Vienna, and her project GLITCHBODIES, which received an honourable mention for New Animation Art at the Prix Ars Electronica the following year. It was an interactive game that combined new forms of feminism, LGBTQ+ and drag.’

The Vatican Museums, the Louvre, a guest performance

In November 2022, Unesco’s World Heritage Convention celebrated its 50th anniversary. ‘There were conferences and exhibitions around the world celebrating world heritage as a source of resilience, humanity and innovation.’ A few weeks earlier, in September 2022, the international media art scene gathered at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz.

‘We were really looking forward to this festival,’ recalls Michaela Wimplinger. ‘Thanks to the support of the Embassy of the Holy See in Rome, we were able to show gigapixel images of two works of art by Pietro Perugino from the Sistine Chapel in Deep Space together with the Vatican Museums. The works were explained by Director Barbara Jatta herself and Rosanna Di Pinto, Head of the Vatican Museums‘ Images and Rights Department.’

The second project was also high-calibre in every respect: an interactive immersive presentation of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’. ‘Vincent Delieuvin, Chief Curator of 16th century Italian painting at the Louvre, Roei Amit, General Manager of Grand Palais Immersif, and Christelle Terrier, Head of Production Mona Lisa Immersive, came to Linz and created a sensational session in Deep Space,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘The collaboration with the Grand Palais Immersif Paris and the Musée du Louvre was fantastic, and the Institut Francais d’Autriche and the French Embassy also supported the project with great commitment.’

Venetian transience, Goya’s truth, Leonardo’s Last Supper

In 2023, the cultural heritage shone brightly once again in ‘Deep Space 8K’. ‘Whether the palazzi and canals of the lagoon city, St Mark’s Square or the walls and ceilings of the Doge’s Palace – “Venice Revealed” amazed everyone,’ Michaela Wimplinger continues to enthuse. ‘The huge three-dimensional model of Venice was created through the collaboration of Grand Palais Immersif, Iconem and Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. Thanks to the Institut Francais d’Autriche and the French and Italian embassies in Vienna, we were able to bring ‘Venice Revealed’ to Linz.’ But that was not all.

‘Supported by the Spanish Embassy in Vienna, we presented gigapixel images by Francisco de Goya together with the Museo Nacional del Prado,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘In a super exciting session, Alejandro Vergara, curator at the Prado, and Javier Pantoja Ferrari, CDIO at the Prado, explained Goya’s work and thinking and repeatedly made references to the theme of the Ars Electronica Festival, which was dedicated to the question “Who Owns the Truth”.’

Furthermore, an equally exciting contribution was shown with the help of gigapixel technology, this time at the Reina Sofia Madrid. Two important works (Pablo Picasso’s Woman in Blue and A World by the artist Ángeles Santos) from the collection of the Museo Reina Sofía were analysed by Olga Sevillano Pintado and Raul Martinez. This was once again made possible by the great support of the Spanish Embassy.

The fourth programme of 2023 was ‘Last Supper’ by Franz Fischnaller and Haltadefinizione. The special thing about it was that you could not only zoom into this ultra-high-resolution gigapixel image of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ and discover the smallest details, but you could even penetrate the two-dimensional plane of the fresco and virtually move around the painting. ‘You could walk around the table where Jesus and the apostles ate their last meal together.’

Cultural heritage, Ars Electronica, 2024

So much for the long, short story of how cultural heritage found its way into ‘Deep Space 8K’ and became an integral part of the Ars Electronica narrative around art, technology and society over the years. But what is being planned for the 2024 Ars Electronica Festival and with whom?

Notre Dame opens its doors

‘First of all, once again I can hardly wait for September to finally arrive and for us to be able to invite visitors back into “Deep Space 8K” as part of the festival,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘Together with Iconem Paris and Histovery, the Institut Francais d’Autriche, the Institut Francais d’Paris and the French Embassy, we will be presenting an ultra-high-resolution 3D model of Notre Dame.’ Every corner of the world-famous cathedral, which caught fire in April 2019, was scanned, photographed and filmed to create this model. The scans by art historian Andrew Tallon, who died in 2018, were of central importance. ‘The Paris-based start-up Iconem then developed a sensational 3D model from this huge amount of data, which is now being processed by the Ars Electronica Futurelab for “Deep Space 8K”,’ explains Michaela Wimplinger. ‘Not least because Notre-Dame in Paris will be reopened with great pomp on 8 December this year, it is simply perfect that we can offer a virtual tour of the cathedral in advance in September and also have internationally renowned experts as guides.’

Vittore Carpaccio’s young knight poses in a picturesque landscape

A second project is being realised with the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza Madrid and the support of the Spanish Embassy in Vienna. ‘We will be showing gigapixel images of Vittore Carpaccio’s “Young Knight in a Landscape” – one of the earliest full-body portraits in European painting, which was long attributed to Alfred Dürer and has now been painstakingly restored,’ says Michaela Wimplinger.

Cultural heritage, Ars Electronica, the future

Art and cultural treasures will form a central theme of the Ars Electronica narrative between art, technology and society beyond 2024. ‘I don’t want to and can’t give anything away yet, but we are holding a whole series of talks with renowned institutions,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘The focus is always on the question of how we can use immersive technologies and different storytelling to open up new and meaningful perspectives on art and cultural treasures. If we can develop satisfactory answers to this question together, we will tackle a project together – if not, then not. Simply taking a picture down and hanging it up again is not worth the effort and will not inspire the public either.’

What motivates her time and again to push ahead with such elaborate projects? ‘Firstly, of course, the fascination that emanates from these works of art. You only have to think about what it means, for example, to write a story that still captivates people 2,000 or 3,000 years later. It’s incredible,’ says Michaela Wimplinger, inevitably going into raptures. ‘On the other hand, I’m inspired by the dialogue with the people who work in all these museums or start-ups. Their enthusiasm for art is boundless and their knowledge is truly impressive. I learn a lot from talking to these personalities.’

What does she find particularly stressful? ‘Overcoming the legal hurdles,’ says Michaela Wimplinger immediately and laughs. ‘Seriously – it’s really not easy to be allowed to show gigapixel images of works like the “Mona Lisa” or to post photos or clips of them online in advance as part of the promo. It’s all about ownership rights, copyrights and usage rights, which can be quite complicated in the case of centuries-old and world-famous works of art.’

Why does she work at Ars Electronica and not in any art gallery or art museum? ‘Because I feel extremely comfortable in the urban, international and diverse world of media art. Issues such as democracy, gender and sustainability are of central importance here and are also extremely important to me,’ says Michaela Wimplinger. ‘When working with such traditional and complex institutions as the Vatican Museums, I always find it exciting to see how and where we find each other – here Ars Electronica, whose world is very fast-moving and confusing due to the rapid development of technology and where all eyes are on the future, and there the world of art history, where everything revolves around the preservation and research of timeless artefacts and where patience and perseverance play an important role. I sometimes get the impression that these collaborations are a link to the past for Ars Electronica and a bridge to the future for the world of art history.’

Media artist Karl Sims (US) founded GenArts in 1996 and developed special effects plug-ins that were used for films such as ‘The Matrix’, ‘Star Wars’ and ‘The Lord of the Rings’. In ‘Deep Space 8K’, his immersive visual worlds meet artistic and technological experiments from past centuries, such as the ‘Tower of Babel’ by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, which in turn inspired the design of Minas Tirith in ‘Lord of the Rings’.

Keyword future. What are her hopes for the coming years? Michaela Wimplinger thinks for a moment and then says: ‘More money and more innovation.’ What does she mean by that? ‘Well, you can never have enough money,’ she laughs, ‘but seriously. Most of the funding for our cultural heritage projects currently comes from the Dorotheum, which has given us great support since 2022, as well as from the embassies and cultural institutions based in Vienna. But it would be great if we could also attract companies as long-term sponsors. Then we would be able – and this brings me to my second point – to explore even more new avenues. I don’t mean more programmes, but more innovative forms of communication and storytelling – for example, I would love to think with international experts about how we could use immersive technologies and appropriate storytelling to present their art and cultural treasures specifically for children and young people. I don’t want to show cultural heritage as a symbol of high culture, but to convey that art and cultural treasures from all regions and cultures of the world are something very human and bear witness to the fact that we have always been very different but also have a lot in common.’