The Lab-Exhibition MATERIA PRIMA presents outstanding work at the nexus of art and science but it is also a showcase for the notoriously curious and as such the whole exhibition space serves as an inspiring laboratory environment which in a literal way has a set of visitor labs as its central core. This hybrid form of presentation is a clear commitment to the didactic and inspirational potential of art and science.

Type: Exhibition

Duration: November 14, 2015 – May 8, 2016

City, Country: Gijón, Spain

Venue: LABoral Centro de Arte

The Lab-Exhibition MATERIA PRIMA presents outstanding work at the nexus of art and science but it is also a showcase for the notoriously curious and as such the whole exhibition space serves as an inspiring laboratory environment which in a literal way has a set of visitor labs as its central core. This hybrid form of presentation is a clear commitment to the didactic and inspirational potential of art and science and an expression of our wholehearted believe in the impact that art and science can unfold beyond their own territories and in the power and creative energy which can be derived from the collaboration of art and science.

Art and Science Join Forces to Respond to the Questions of Our Time

In our present time, which is so essentially dominated by technology, it appears that science has taken over the leading role in culture and in many cases replaced religion. Under these circumstances the growing focus on collaborations between art and science and their greater synthesis seems only logical. Humans will always make art and do science, and this is probably one of the most defining characteristics of our species.

The interrelationship between art and science has been a crucial issue throughout history – you will not find a period in which artists do not strongly refer to science as a source of inspiration or as a topic worth addressing. Many would even claim that in the beginning art and science were not separate fields at all, and that they continue to be motivated today by the same human desires. In our digital age, this issue has again become a very visible, public topic.

New tools for artists

The first wave of interest was triggered by the curiosity of artists, pioneers and avant-garde thinkers and led to their exploring the new tools, their meaning and possible impact beyond technical and industrial applications. The “Cybernetic Serendipity” exhibition (1968), the first Sky Art Conference (1981), the 1986 Venice Biennale and, of course, also the establishment of the Ars Electronica Festival in 1979, are all part of this development. And yet it is very interesting to see that at this early stage only Ars Electronica had explicitly included the impact on society in defining itself as a “festival for art, technology and society”.

The growing attention to biotechnologies, in particular to the race to decode the human genome in the late 1990s, gave birth to a new frontier, one that demanded the even greater commitment of the artist to delve deeply into techno-scientific matters. Moreover, artists emerged who were no longer satisfied with only commenting on the ethical implications of genetic engineering, but who also wanted to be able to work with these very new tools and instruments alongside scientists.

Broad exchange between art, science and technology

Recently the increasing need to respond culturally to the rising power of the computer and the massive invasion of digital ICT in every aspect of our lives has again attracted greater attention to the idea of a close collaboration and broad exchange between art, science and technology. But it is no longer just artists and scientists who are interested in working together; collaborating has also become a topic for the industry and policy-makers.

Which is largely due to the growing popularity of the idea that many of the challenges of our present time can only be solved using creative new approaches and even more extensive collaboration. And of course it is true that the challenges we face as a result of the many changes now taking place are greater than the capabilities of each individual group of experts. Hence collaboration that goes beyond a mere joining of forces but has the potential to lead to transformation and innovation is the mantra of our time. No doubt the attention currently directed towards artistic and scientific collaborations has also been determined by very profane expectations – the hope that a new wave of creative innovations might boost weak economies and provide the much needed competitive edge for the next decade.

It remains to be established whether innovations in science and art are a driving force for or rather a result of cultural and societal transformations. Nevertheless, it is clear that they always go hand in hand. And in times of crisis, when many questions are open and answers are few, the focus shifts to innovative sources of inspiration for new alliances and paradigms. And this is especially true for the times we are living in, when the challenges are bigger than the expertise of any single group.

How can we benefit from this relationship?

- Art and science have always been very close to each other, but now the important point has become how can we benefit from the special energy that emerges from this relationship.

- What are the challenges without compromising the autonomy and integrity of the artistic process? After all, this process is the one thing that makes it so promising and valuable.

- What kind of practices might be established to successfully tap into this special energy? How can it be translated and conveyed beyond art? How can art itself benefit from this and gain innovative momentum? What experiences and findings can be drawn from the prototypical encounters and collaborations of the many artists in residence programs that are currently aiming to bring artists and scientists together?

These are the questions that are presently being discussed in many programs and places, and for this reason Ars Electronica organized for six experienced European art institutions to team up with two of the most exciting research facilities existing today. CERN with its Large Hadron Collider that probes the smallest constituents of matter, and ESO’s high end observatories in Chile that study objects at the farthest reaches of the universe. In addition to these unique opportunities for artists-in-residence, a series of international exhibitions is being organized. LABORAL’s exhibition MATERIA PRIMA is the main event.

The LabExhibition as an experiment

But MATERIA PRIMA is not just an exhibition, at least not an ordinary exhibition, it is an experiment on its own, an attempt to create access, to blaze trails into the vast overlapping territories of art and science. Above all it aims to achieve a new level of visitor involvement and participation. What could be more appropriate than a place like LABoral, which itself is exemplary for a new type of hybrid and collaborative institution, a center for original artistic creation as well as community-based co-creation. Moreover, it is a platform for knowledge production and education, and an innovative instrument for establishing new directions in research and developing partnerships in the region with local experts.

The title MATERIA PRIMA is a reference to the history of a philosophy in which material prima was considered the first matter or basic starting material from which everything else evolved. For the alchemists of the early ages it symbolized the mystery of the holy grail. They believed if they could discover the materia prima, they would be able to make gold. In a certain way the idea is not all that far fetched, especially if we think of these alchemists as the hackers and DIY makers of their time, explorers at the borders of science, art and mysticism. They defied established knowledge and scientific dogmas, and did not shy away from taking unorthodox and forbidden paths to gain greater insight. After all, breaking the rules is the only way to get things right, especially when the rules are wrong or insufficient. And although we might call them fools for aiming at the impossible, along the way they created many by-products, maybe even more than produced by the race to the moon.

In our times it is data that has become the equivalent of materia prima. For it is now the basic and universal material which may be translated or transformed into anything else. Moreover, it has become the seemingly inexhaustible raw material for everything, including the spectacular business models that have given rise to some of the most profitable business ever. So it seems to be true that if you just find the proper materia prima, you can even convert it into gold – that is, the gold of our time, stock options for the next most promising start-up.

MATERIA PRIMA LabExhibition presents outstanding work at the nexus of art and science, while also providing a showcase for the notorious curious. The whole exhibition space serves as an inspiring laboratory environment that has a set of visitor labs literally at its core. This hybrid form of presentation is a clear commitment to the didactic and inspirational potential of art and science. It is also an expression of our wholehearted belief in the potential impact of art and science to go beyond their present territories, as well as our belief in the power and creative energy that can be derived from their collaboration.

“Materia prima, or raw material, speaks to the essence of things, the starting point, what remains inalterable, the most important core reflection on which we base the construction of our surrounding environments.”

Read an interview with Lucía García Rodríguez, the Managing Director of LABoral, on the Ars Electronica Blog. She talked about her understanding of the term Materia Prima, about the exhibition itself that is structured in several laboratories and recently opened in Gijón and about the Spanish view of the connection between art and science. www.aec.at/aeblog

Projects

The core of the exhibition consists of a set of interactive visitor labs. Education and communication are not a side program but the central component in this exploration of art and science. The labs are surrounded by exploratory displays featuring outstanding artistic works as well as R&D prototypes – atelier and laboratory meld together here. In between these areas, we find references to the rich history of the liaison of art and science.

To quote Merriam-Webster dictionary, a laboratory is “a place providing opportunity for experimentation, observation, or practice in a field of study”. Although in our common understanding of laboratories, we tend to see them as places where highly secret experiments are conducted and high-cost equipment is used. Places where access is only granted to those who have a good relationship to the people working there or a mandate to enter them. They are where processes take place that have a direct impact on knowledge.

Exhibition setting focuses on laboratory structure

MATERIA PRIMA is an exhibition concentrating on artistic/scientific processes and the generation of knowledge in art. Rather than presenting objects, this exhibition focuses on bringing those processes to the surface that confront artists (and sometimes even scientists). The participating artists were asked to work on adapting these processes for presentation within an exhibition context. And in order to underline their process-oriented approaches, it was clear from the beginning that we, as curators, should try to leave a so-called classical contemporary presentation of artworks behind us and create an exhibition setting that focuses on laboratory structure. But not only the systematic processes inherent in the artworks were to be explored in this way: more importantly, the laboratory – as site of experimentation, observation and practice – was to be brought into the exhibition space and made accessible to visitors.

Of course this approach is not new and we have been testing this kind of laboratory structure since January 2009 in our own Ars Electronica Center in Linz. For seven years now we have been displaying, discussing and making practices accessible that are the focus of artists, scientists and technologists. It goes without saying that a citizen’s lab cannot, for example, include the entire diversity of existing laboratories or their high-end equipment. Nor can it meet the requirements of sophisticated scientific research. However, we can make experiments visible, discuss observations and enable participants to gain some practice with the machines and processes on display: these are the parameters that we set and that guided us in our approach to establishing a laboratory structure within an exhibition context.

In sifting through the diversity of artistic practice to be presented in the MATERIA PRIMA exhibition, we divided the works into six labs based on the phenomena which the artists had chosen to focus on. Each lab represents a selection of the artworks on display, and showcases them via images and texts that are related to the central topic of the lab.

BioLab

The Biolab is represented by six works that explore recent questions in genetics.

“Drosophila titanus” by Andy Gracie (UK/ES) is an ongoing and long-term project which through a process of experimentation and artificial selection aims to breed a species of the fruit fly, drosophila, that would theoretically be capable of living on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The project needs to adhere to a rigorous scientific methodology and framework in which the artist can act and at the same time artistically investigate concepts related to the topics of species, biological perfection, perception and future life.

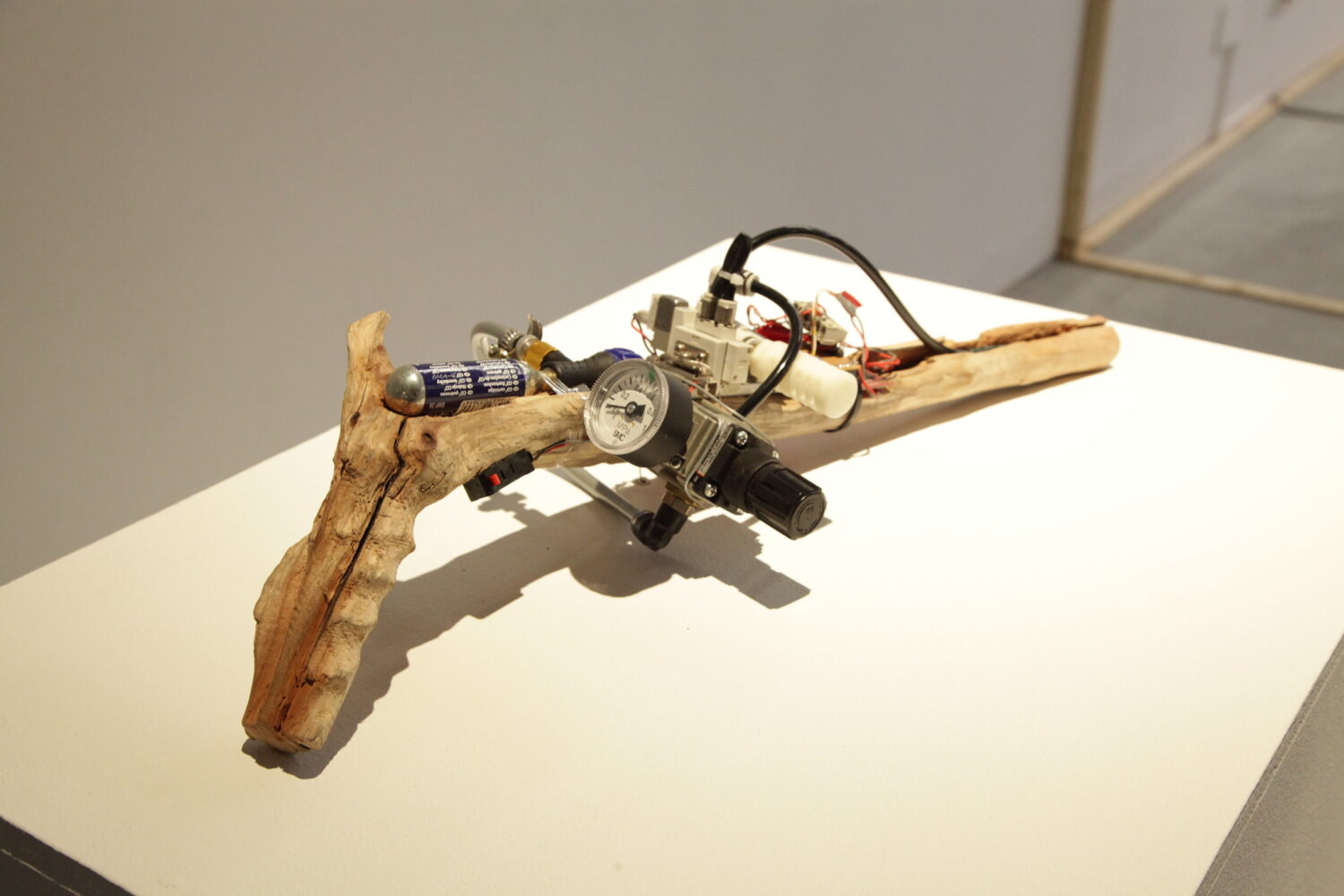

“Gene Gun Hack” by Rüdiger Trojok (DE) is a scientific instrument. The biologist Rüdiger Trojok succeeded in building one of his own and in slashing its cost to a mere 50 euros. Normally the gene gun is one of the most important tools used in modern biology. Many of today’s genetically modified plants have been produced with this technology, which is a kind of a bio-ballistics device used to shoot a particle of gold coated with DNA into a cell. Trojok has not only provided a DIY version of a gene gun, he has at the same time critically questioned developments in genetic engineering.

Similar to Trojok, the artist Matthew Gardiner (AU) was inspired by the idea of using a gene gun in a similar way as the British police are said to use them: DNA sequences containing particular codes are deployed to mark suspicious persons with a shot from a special pistol. In his work “Synthetic Memetic”, Matthew Gardiner composed a DNA sequence in such a way that the series of nucleotide bases in it correspond to the letters of the song title “Never Gonna Give You Up” by Rick Astley, and then integrated them symbolically into a pistol. It is a reference to the viral systematics of this song that – having first topped charts worldwide in the 1980s – is still causing a commotion online: users who click on some seemingly innocuous headline, image or video are unexpectedly redirected to Rick Astley’s catchy tune.

Teresa Dillion (IE), Naomi Griffin-Murtagh (IE), Claire Dempsey (IE) and Aisling McCrudden (IE) are artists who once came together for a course on synthetic biology and posed the following question: Can animals be transformed into medical devices? “Opimilk”, as this Dublin-based team calls their idea, involves transforming the bovine organism into a living bioreactor, and so producing complete and effective medications that can be milked right from the cow’s udder.

Based on DNA systematics, a group of Ars Electronica Futurelab researchers asked during an “ARS DNA” workshop, how digital data might be stored to memory for 10, 100 or even 1,000 years without having to transfer it periodically to new data storage media? Now this question is not new, and so numerous labs are already working on it. But then the importance of this idea was transferred to a workshop with citizens in Linz and then to one in Gijon, where audiences were invited to understand the latest research on DNA as a medium for memory, as well as to convert their name or some other series of characters into a DNA sequence. Simultaneously they were asked to investigate how much they would have to pay today to have this done in a lab.

“Biopresence” by Shiho Fukuhara (JP) and Georg Tremmel (AT) creates “Human DNA Trees” by transcoding the essence of a human being within the DNA of a tree in order to create “Living Memorials” or “Transgenic Tombstones”. “Biopresence” is collaborating with scientist and artist Joe Davis on his “DNA Manifold algorithm”, which allows for the transcoding and entwinement of human and tree DNAs.

FabLab

The idea of making high-tech processes and flexible manufacturing equipment accessible to visitors is, of course, part of the exhibition concept. Hence LABoral’s existing FabLab – and all its machines, tools and equipment – has been transferred to the exhibition floor. In workshops visitors will be trained to use them, and in doing so become part of this discursive exhibition project. In addition, the FabLab should provide inspiration to participants via the artworks on display and/or the artists working there.

Asturian artist María Castellanos and Madrid native Alberto Valverde are two of the artists who will work in the FabLab during the exhibition. They will explore certain man-machine relationships and intersections. Their work “Environment Dress” focuses on garments as a kind of sensory device for investigating variations in noise, temperature, atmospheric pressure, ultraviolet radiation or the amount of carbon monoxide we are exposed to in our daily life. The person wearing this smart dress will receive direct feedback about his or her exposure through changes in the dress’s lighting.

Another artwork on display is by Belgian artist Nick Ervinck. For “AGRIEBORZ” he used images of human organs that he found in medical manuals as construction material for creating organic forms, and then realized them in 3D. With his work he is questioning, on the one hand, the impact of rapid prototyping and 3D printing for medical research and, on the other hand, the influence of bioprinting technology in generating organs. Ervinck, who is working parallel to science, is developing new realities for different audiences in art, science and beyond.

DataLab

You might be wondering what the purpose of a data lab is? Isn’t data rather the outcome of a lab, the result and not the experiment? But when we look at how data has become the raw material of a new economy and the basis of a new culture, we see how important it is now to understand the technologies used to process data, the social and economic value of it, as well as the very special nature of digital data itself.

Digital data is like its own aggregate state, not of matter but of information; it is a distinctive type of information that takes on a distinctive form of appearance as soon as it becomes digital. In other words, when it is set free from physical boundaries as code, as a series of zeroes and ones that can be endlessly copied and distributed and transformed into any thinkable form of expression from words to sound to image, and with 3D printing even to physical objects.

The computer has become our universal memory machine and being able to deal with the very special powers of data has now become an ever more important skill. And this goes beyond mere media literacy; it involves the kind of understanding that enables you to become a creator instead. This section features artistic and scientific projects dealing with transformations between the virtual and physical state of data.

Agnes Mayer Brandis’s “Teacup Tools” are part of a “Global Teacup Network” and draw attention to climate-related sciences. Her work consists of a table and machinery for raising two or more teacups individually. Various measuring instruments are built in and onto the tea cups, measuring the environment of the cup. The energy produced by these instruments heats the inside of the cups and brews tea from rainwater and the residues that have fallen into it. This tea produces a little cloud that contains the essence of the local air. The cloud again feeds back into the system and becomes the subject of investigation for the tools connected to the cup. The teacups move up and down individually, according to certain aspects related to the collected data and environmental processes, dancing an endless choreography determined by raindrops and clouds, particles, measurements and tea drinking.

Another data collecting project is “ARTSAT1:Invader”, which was launched on February 28, 2014 (JST). It was the world’s first art satellite sent into orbit as a piggyback payload onboard the H-IIA F23 launch vehicle, and inserted into a non-sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of 378 km and inclination of 65 degrees. Invader, a 10-cm 1U-CubeSat with a mass of 1.85 kg, continued its steady operation in orbit. It also successfully performed an array of artistic missions based on commands from the main ground station at Tama Art University and under the guidance of the “ARTSAT: Art and Satellite Project” team. The mission included algorithmic generation and transmission of synthesized voices, music and poems, as well as capturing and transmitting image data and communicating with the ground through a chatbot program.

Visualization Lab

Beside the fact that the artists in the DataLab have a very strong relationship to the visualization of their data, we wanted to focus here on the diversity of visualization processes, in particular when it comes to the question of visualizing scientific topics and the socio-political impact of visualizing data, as well as the artist as subjective interpreter.

Since 1968, scientist-artist Cornelia Hesse-Honegger (CH) has been painting pictures of flies and other bugs that have mutated as a result of environmental contamination and atomic radiation. Since the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986, she has collected more than 16,000 insects in the fallout zones of Chernobyl and nuclear facilities in Asia, Europe and the US under the title of “Seh-Forschung” (vision research). She calls her approach “knowledge-art” and is still continuing her work on it. In October 2015, she received the Nuclear Free Future Award in the category education.

Jon McCormack’s Fifty Sisters are the counterparts of Cornelia Hesse-Honegger’s handmade drawings. Since the late 1980s McCormack has worked with computer code as a medium for creative expression. Inspired by the complexity and wonder of a diminishing natural world, his work is concerned with electronic “post-natures” – alternate forms of artificial life that may one day replace the biological nature lost through human progress and development. Fictional visualization is also practiced by the artist Nick Ervinck, who was presented earlier within the context of the FabLab. At first sight his 3D printed objects look as if they have been made for medical research, however, as soon as you understand that his work is not about existing bodies, you start imagining the creatures behind the objects on display.

GeoLab

Space and time related data and phenomena in physics and mathematics are the main parameters defining the MATERIA PRIMA’s GeoLab. All the artworks presented here can be seen as an experiment in visualizing causalities and correlations on earth and beyond.

María Ignacia Edwards (CL) “Mobile Instrument”, for example, works with equilibrium, lightness, and the weightlessness of objects, which she brings into balance by deploying their own weight or counterweights. Though, at first glance, her works are perceived as purely aesthetic, artistic objects, it soon dawns on those who behold them that these constructions are the result of elaborate mathematical and physical calculations, mechanisms, solutions and interventions. María Ignacia Edwards calls these pieces self-sustainable because they require no more than their own weight to exist, and the objects tend to rotate constantly around their own axis.

“Chijikinkutsu” by Nelo Akamatsu (JP) is a coinage, combining two Japanese words: Chijiki means geomagnetism. It is about terrestrial magnetic properties that have always existed and affect everything on earth, even though they cannot be perceived by the human senses. A “suikinkutsu” is a sound installation for Japanese traditional gardens, invented in the Edo period. The sounds of drops of water falling through an inverted earthenware pot buried under a stone washbasin resonate through hollow bamboo tubes. Chijikinkutsu is made using water, sewing needles, glass tumblers and coils of copper wire. The needles floating on the water in the tumblers are magnetized in advance, so they are affected by geomagnetism and turn themselves in a north-south direction. When electricity is supplied to the coils attached to the outside of the tumblers it creates a temporary magnetic field that draws the needles to the coils. And the faint sound of the needles hitting the glass resonates in the space all around.

Acoustic levitation is the secret behind “Lapillus Bug” by the three Japanese artists Kono Michinari, Takayuki Hoshi and Yasuaki Kakehi. Similar to a fruit fly, Lapillus Bug flits about over the table, interacts with people, and reacts to light and motion. But here’s the interesting part—it’s just a Styrofoam particle kept aloft by sonic waves out of the range of human hearing. Ultra-low frequencies produce standing waves that let the little bug hover – thanks to a phenomenon called acoustic levitation. The point of this work is to breathe life into an inanimate object by means of external forces.

Philosophy Lab

While the labs depicted so far have had primarily to do with practices, methods and processes in art and science, we want to conclude by discussing the role of the artist/scientist/citizen, and robot or machine. Confronted with the situation that machines are assuming ever more responsibilities, we need to recognize that it is still we humans who have to program them, and to code algorithms based on our experiences and knowledge. But what if in complex situations machines have to decide between life and death? Or whether to help others or themselves? Or to aid an old person or a child? What does responsibility during scientific or artistic processes mean within the context of technological developments?

The excursive project “Transferences –Arts, Sciences and New Forms of the Local” by Lorena Lozano (ES) puts forward the idea of the plurality of the arts and sciences, and the need to generate collaborative processes of knowledge transference to strengthen common knowledge. This laboratory is an open office, a participatory and propositional place for active listening and rethinking the role of artists and researchers. The activities in this lab develop in six open encounters that include presentations, interviews and debates.

In addition to Lozano’s excursive project, Patricia Piccinini is presenting “The Listener”. This humanoid figure that her crew painstakingly put together out of silicon, fiberglass and human hair doesn’t seem the least bit threatening. Actually, its vulnerability is what leaves the strongest impression. With a friendly look on its face, it seems to be seeking acceptance and hoping that we are not put off by its strangeness. In a world in which human beings can use new technologies to modify and reform the creatures of nature, in which the diversity of life has reached a new stage, and in which new possibilities of synthetic biology bring forth more questions than answers, we mustn’t lose our capacity for empathy. And so the question arises: Can a code for empathy be written for a machine and if so, what challenges will we have to face in the future?