What is ‘green’? Are we ‘green’? And is it the vegetative world at all? Are algae ‘superfoods’, environmental pests – or both? Is biodiesel green? Beyond the rampant ‘greenwashing’ of our times, artists and scientists in this symposium get to the bottom of the increasingly uncritically accepted symbolism of ‘green’ – as a RE-mix and RE-evaluation of contradictions and paradoxes. Engineers praise ‘green’ chemistry or biotechnology as ecologically benign, while climate researchers, on the other hand, bemoan the ‘greening of the earth’ as an alarming sign of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, and toxic algal blooms discredit the overused association of ‘green’ with sustainability. Is ‘green’ perhaps so important to us because naturalness and artificiality, the healthy and the toxic, the hoped-for and the lost oscillate here? Is ‘green’ perhaps even itself a ‘presumptuous’ or ‘pretentious’ color, whose casual symbolic use should be increasingly questioned? The panel contributions discuss art on the threshold of the techno-sciences, and emphasize the material factors of what appears to us as ‘green’ – but no longer just metaphorically but above all metabolically!

Video

Schedule

| 14.00 – 14.15 | Welcome Address: Why gREen at Muffatwerk? Dietmar Lupfer, Muffatwerk München |

| 14.15 – 14.45 | Greenness: Sketching the Limits of a Normative Fetish Jens Hauser, University of Copenhagen/Medical Museion |

| 14.45 – 15.15 | Have a tea with a tree Agnes Meyer-Brandis, Artist, Berlin, FFUR Institute for Art and Subjective Science |

| 15.15 – 15.45 | The scent of trees: A volatile alphabet for communication with their environment Jörg-Peter Schnitzler, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Research Unit Environmental Simulation (EUS) |

| 15.45 – 16.00 | Break |

| 16.00 – 16.30 | Green Unicorns Thomas Feuerstein, Artist, Vienna |

| 16.30 – 17.00 | Shadows from the Walls of Death: Re-Mediating Green Adam Brown, Artist, East Lansing, Michigan State University |

| 17.00 – 17.15 | Break |

| 17.15 – 17.45 | Roscosmoe: Why did the sea worm want to go to space ? Ewen Chadronnet, Makery, Paris |

| 17.45 – 18.15 | Becoming Homo Photosyntheticus. A speculative fabulation Maya Minder, Green Open Food Evolution, Zürich |

| 18.15 – 19.00 | Wrap-up & Discussions |

Speakers and Abstracts

Jens Hauser

University of Copenhagen/Medical Museion

Greenness: Sketching the Limits of a Normative Fetish

Are we ‘green’? The entanglement between symbolic green, ontological greenness and performative greening poses challenges across disciplines that provide an epistemological panorama for playful debunking: ‘green’, symbolically associated with the ‘natural’ and employed to hyper-compensate for what humans have lost, needs to be addressed as the most anthropocentric of all colours. There has been little reflection upon greenness’ migration across different knowledge cultures, meanwhile we are green-washing greenhouse effects away. Indeed, a morbid odour clings to the charm of the pervasive trope of greening everything, from mundane ‘green burials’ to transcendental ‘greening of the gods’, and even ‘green warfare’, taught in Military Studies. Despite its, at first sight, positive connotations of aliveness and naturalness, the term ‘green’ incrementally serves the uncritical, fetishistic desire to metaphorically hyper-compensate for a systemic necropolitics that has variously taken the form of the increasing technical manipulation of living systems, ecologies, the biosphere, and of very ‘un-green’ mechanisation. Paradoxically, green plays a central role in human evolution and self-understanding – as colour, percept, medium, material biological agency, semantic construct, and ideology. In its inherent ambiguity, between alleged naturalness and artificiality, employed to reconcile humans with otherness as such, greenness urgently needs to be disentangled from terms— both putatively non-technological—such as ‘life’ and ‘nature’.

____

Agnes Meyer-Brandis

Artist, Berlin, FFUR Institute for Art and Subjective Science

Have a tea with a tree

The presentation will focus on my artistic research at various climate and forest research stations over the course of many years, especially on the specific communication systems used by trees, and on the phenomenon of migratory trees and other wandering ‘green’ species due to climate change. While trees are rooted, long-term observations have shown that forests actually move throughout the landscape and regions – just very slowly and over decades. However, climate change appears to happen faster than the trees can escape to more suitable areas in order to survive. Scientists are therefor discussing “assisted migration” in order to help speeding up the process of tree adaption. But in order to safe trees we first need to gain a better understanding of what a tree is, does, and how it communicates. Like humans, trees and plants have their individual scent. Plants emit and communicate via Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) – gases and molecules that contribute to cloud formation, which we recognise as the fragrance of a forest. This paper discusses the artistic project One Tree ID, which condenses the olfactive identity of a specific tree into a complex perfume that enables human visitors to apprehend the tree’s communication system at a biochemical level.

____

Jörg-Peter Schnitzler

Helmholtz Zentrum München, Research Unit Environmental Simulation (EUS)

The scent of trees: A volatile alphabet for communication with their environment

Plants, especially trees, synthesize and emit a large variety of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). VOCs, mainly from the group of terpenoids such as isoprene, mono- and sesquiterpenes, play important roles in atmospheric chemistry as reactive compounds contributing to urban photosmog and aerosol formation, and as climate relevant greenhouse gases. In humans, they are of great importance as scents, kitchen spices or as components of biological pharmaceuticals. The VOC profiles of different organs of trees, e.g. leaves, flowers, bark or roots are different and also differ between different tree species. For trees as sessile organisms, information transfer from plant to plant is an important component of adaptation to increase stress resistance. Trees are in constant material exchange with themselves and the environment and release a large part of the carbon fixed by photosynthesis through respiration, root exudates, symbiosis with mycorrhizal fungi or in the form of VOC emissions. The “scent of trees” is not always the same, but adapts to changes in the environment. In the “wood wide web” of forest ecosystem individual VOCs can be understood as individual letters of a volatile alphabet, which helps plants to exchange information with each other or with insects, fungi and bacteria. The lecture gives an insight into the world of VOCs of trees, but also fungi and shows how these compounds are used in nature to warn each other of pests, to attract helpful insects or to defend themselves against microbes and fungi.

____

Thomas Feuerstein

Artist, Vienna

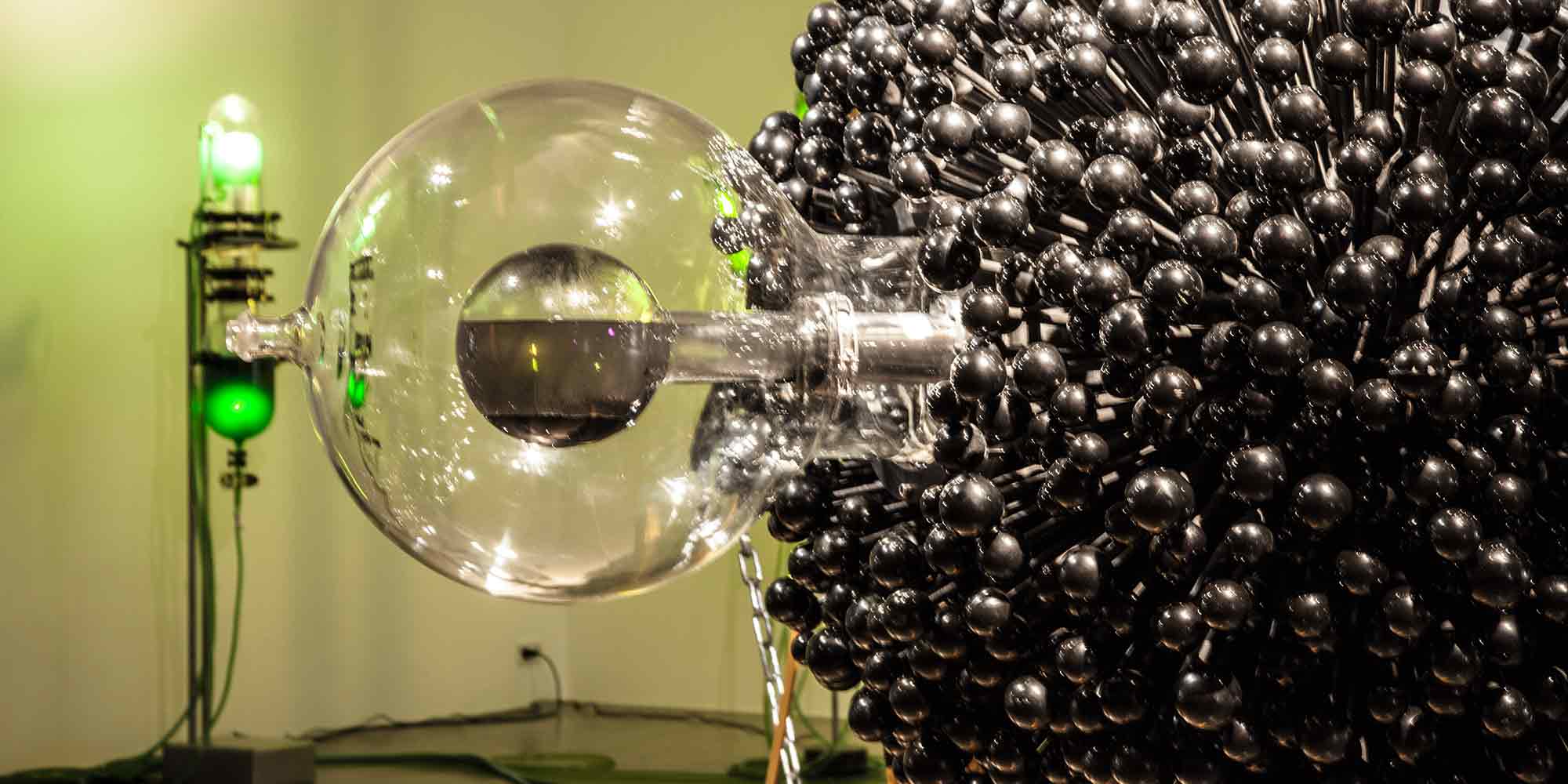

Green Unicorns

A flowerpot, a petri dish or a bioreactor are all small types of a hortus conclusus, the enclosed paradisiac green garden. Medieval representations of the hortus conclusus often contain a unicorn that stands in as a symbol for the maiden and pure nature. The “new unicorns” growing in laboratories are not only immaterial imaginations. They constitute the real matter of incarnated ideas. “Unicorns” are still fabulous objects but they awake to life. But a “unicorn” isn’t a mere metaphor or allegory in art any longer. And art isn’t any longer a semiotic system only. Art becomes a metabolic system. This is the crucial point: It has the capacity to make fine art contemporary and specific. Metabolisms enable art to enter reality; they connect artworks with processes in nature and society, and our daily life. An artwork is a clash of the symbolic realm and the realm of the real. Only the transformations and translations between those spheres bring an artwork into the world. Therefore, green has to be considered as a “metabol,” not just as a colour. It involves metabolic processes and becomes a universal topic ranging from thermodynamics to global economics and the processes in our brain. In art history, green was a symbol, now it becomes a “metabol”.

____

Adam W. Brown

Artist, East Lansing, Michigan State University

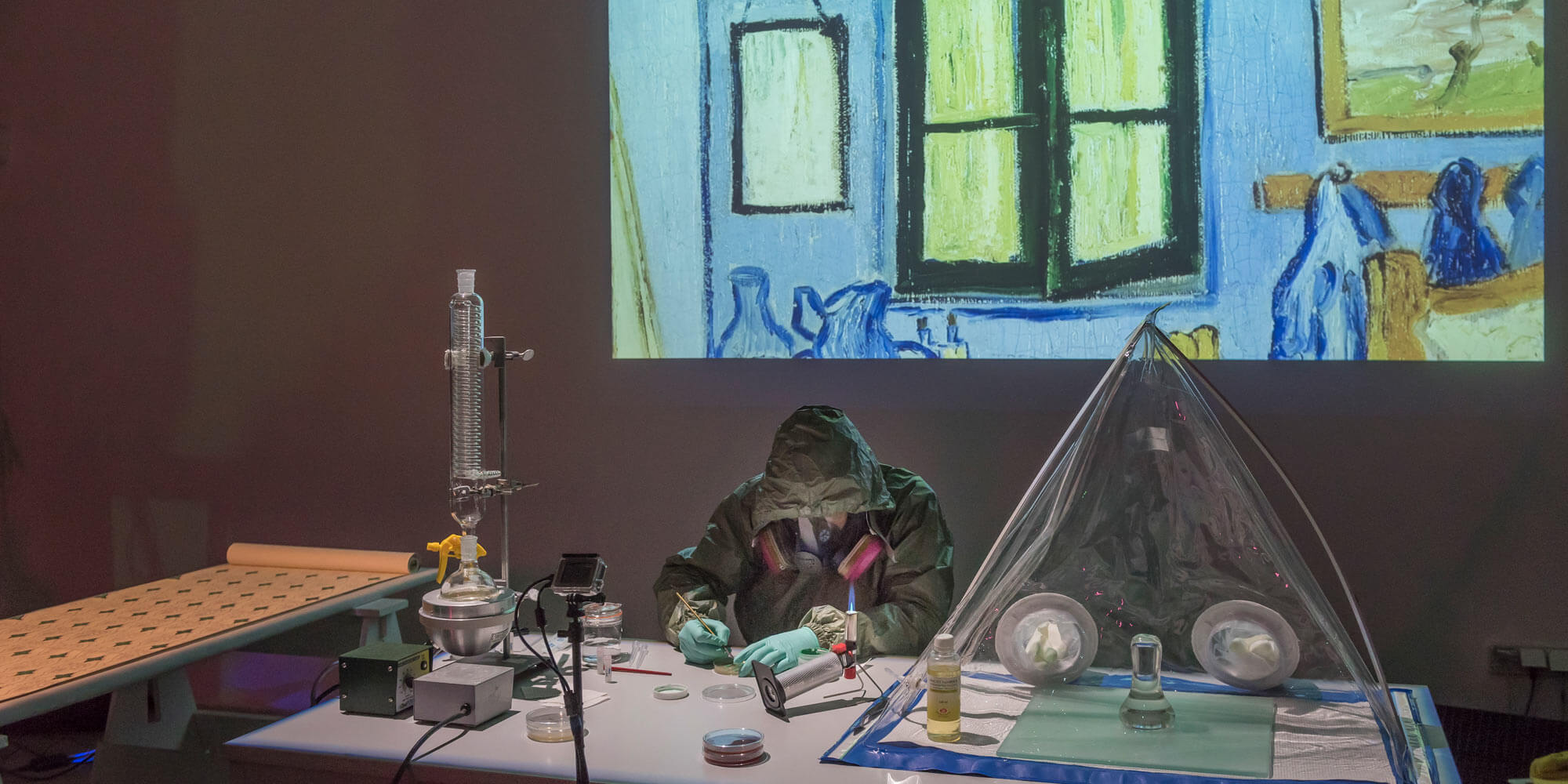

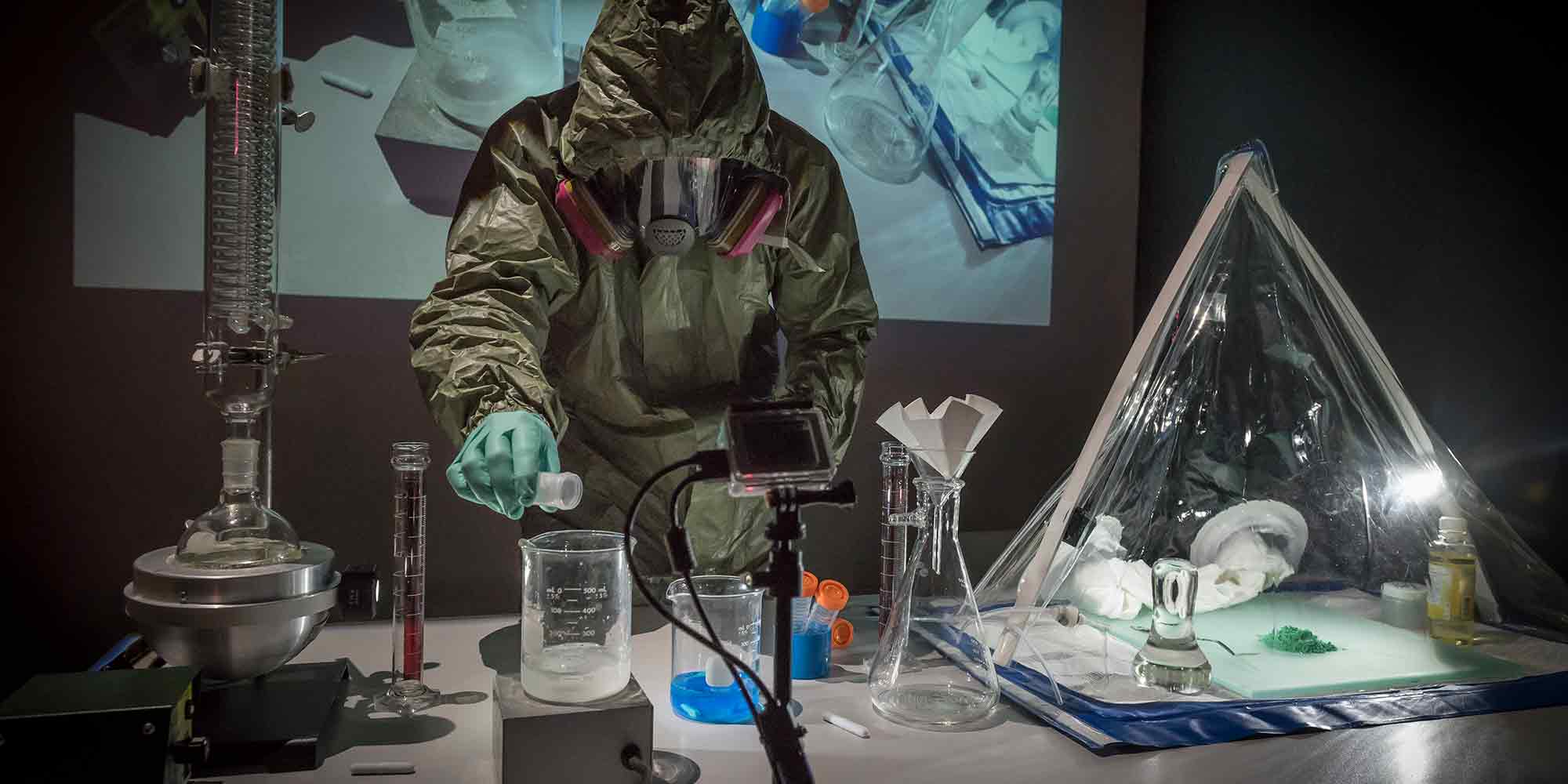

Shadows from the Walls of Death: Re-Mediating Green

Shadows from the Walls of Death: Remediating Green is a series of artworks that deconstructs the symbolic and superficial use of “green” as a pretense, synonymous with ecological and vegetal health, by recreating a highly toxic pigment called Paris Green and deadly wallpaper, thus ironically re-establishing humans’ material connection to the color green. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries had given rise to modern cities removing humans from an entangled connection with nature. The human drive to recreate greenness within urban settings led to a series of paradoxes: The very chemical processes artificially employed to bring greenness back into people’s lives paralleled the anthropogenic destruction of the environment. Mass produced toxic pigments were used in printed wallpaper, and even as a colorant for candy to replace the ‘nature’ that the Industrial Revolution was eroding. In the performance Shadows from the Walls of Death, Paris Green is synthesized to reproduce the deadly wallpaper. Finally, Van Gogh referenced images are painted in Paris Green, to be bioremediated and detoxified by bacteria and fungi-based micro ecologies. Microecologies capable of detoxifying arsenic exist due to the ecological principle summarized by the Baas Becking hypothesis: ‘Everything is everywhere, but the environment selects.’ Non-human micro ecologies not only help us out of this toxic environmental predicament but also deconstruct ontologies acknowledging only human individuality.

____

Ewen Chadronnet

Makery, Paris

Roscosmoe: Why did the sea worm want to go to space?

The interdisciplinary artistic research project Roscosmoe – The worm that wanted to go into space aims to develop a series of experiments and bio-regenerative autonomous habitat designs to assess the behaviour of the photosymbiotic marine worm Symsagittifera roscoffensis in various gravitational environments, including zero gravity conditions. It links the fields of marine biology, space research, anthropology of science, design and intermedia art. Symsagittifera roscoffensis is a green, exceptional marine worm, a “plant-animal” 3 to 4 mm long living on the Breton coastline. It shelters micro-algae under its epidermis, which, in turn, supply the essential of the worm’s nutritive contributions by its photosynthetic activity. This partnership is called photosymbiosis – from photo, “light” and symbiosis, “living together”. These photosynthetic marine animals live in colonies on the tidal zones of the Atlantic coast. The specific biological features of Symsagittifera roscoffensis makes this marine species a potential model for the development of bio-regenerative life-support systems applied to space research.

____

Maya Minder

Green Open Food Evolution, Zürich

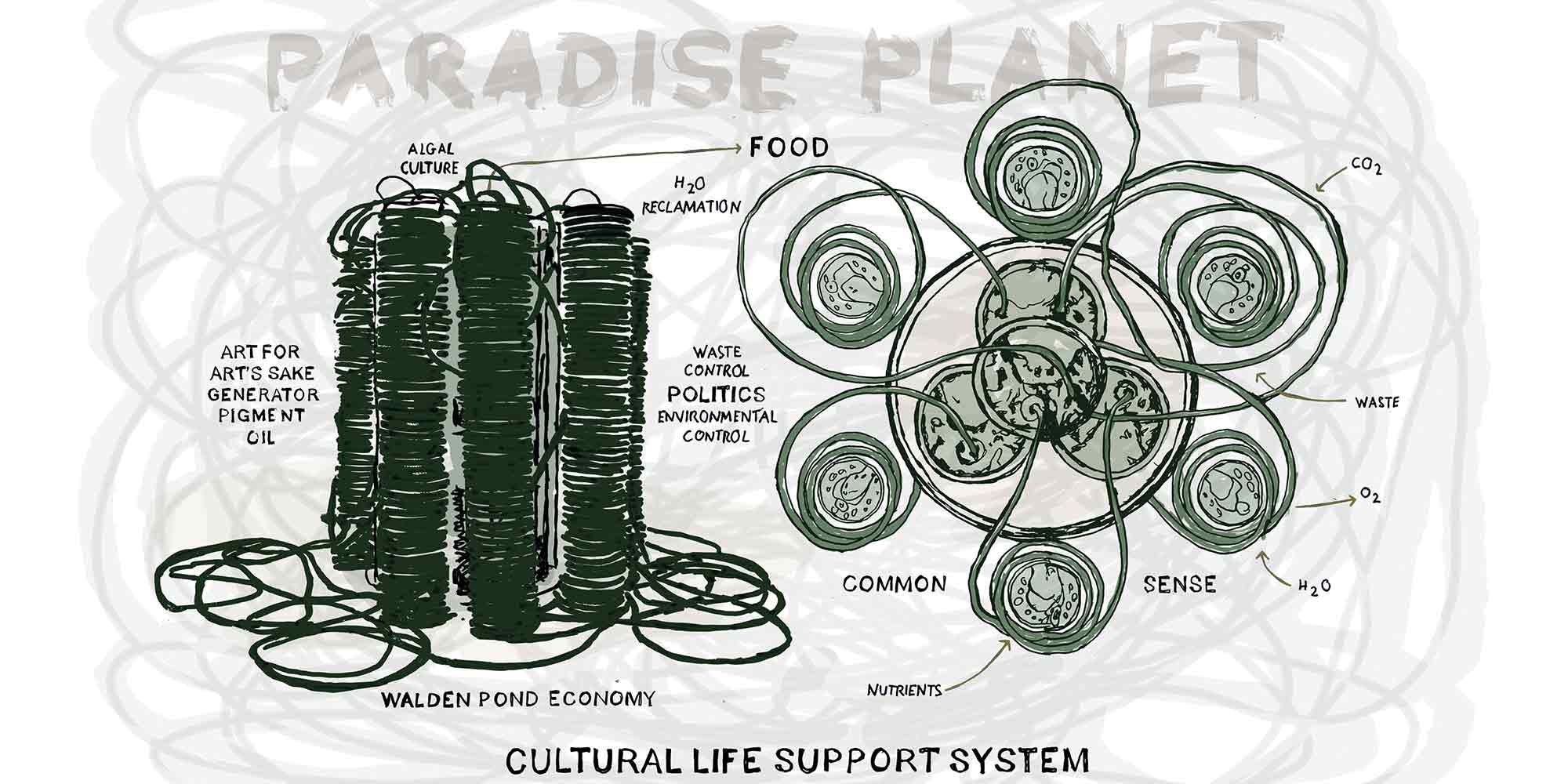

Becoming Homo Photosyntheticus. A speculative fabulation

Green Open Food Evolution proposes a speculative narration into possible dietary programs based on algae rich nutrition, aimed at rewriting the human holobiome so to ultimately become Homo Photosyntheticus. Scientific research has recently discovered how the intestinal microflora of Japanese people has adapted to digest Nori seaweed: a gene transfer occurred between an ancestral marine bacterium and an intestinal bacterium specific to the Japanese. Once ingested by Japanese people, marine bacteria associated with algae were then able to come into contact with intestinal bacteria and transfer their “utensils” to them. Would our own intestinal bacteria be able to acquire the same features today as the intestinal bacteria of the Japanese if we regularly ate raw seaweed-based foods? This discovery of the “sushi factor” may be only the beginning of a wider field of investigation into the evolution of the human holobiont and its possible future. What would happen to Homo Photosyntheticus, a sort of ultimate vegetarian who no longer eats but lives on internally produced food from his algae symbiosis? Our Homo Photosyntheticus descendants might, with time, lose their mouths, becoming translucent, slothish, and sedentary.