Metalens

by

Johanna Einsiedler & Linas Vaštakas

Concept

In a world of information overload, finding information on a certain topic is not a problem. The real challenge is making sense of the available information. This is also true for scientific knowledge: since 1996 more than 45 million articles have been published in scientific and technical journals and every year over 2.5 million new ones are added.1 This makes it increasingly hard to find evidence-based answers even to simple questions.

In our project, we posed ourselves the question: is it possible to make finding science-based answers easier?

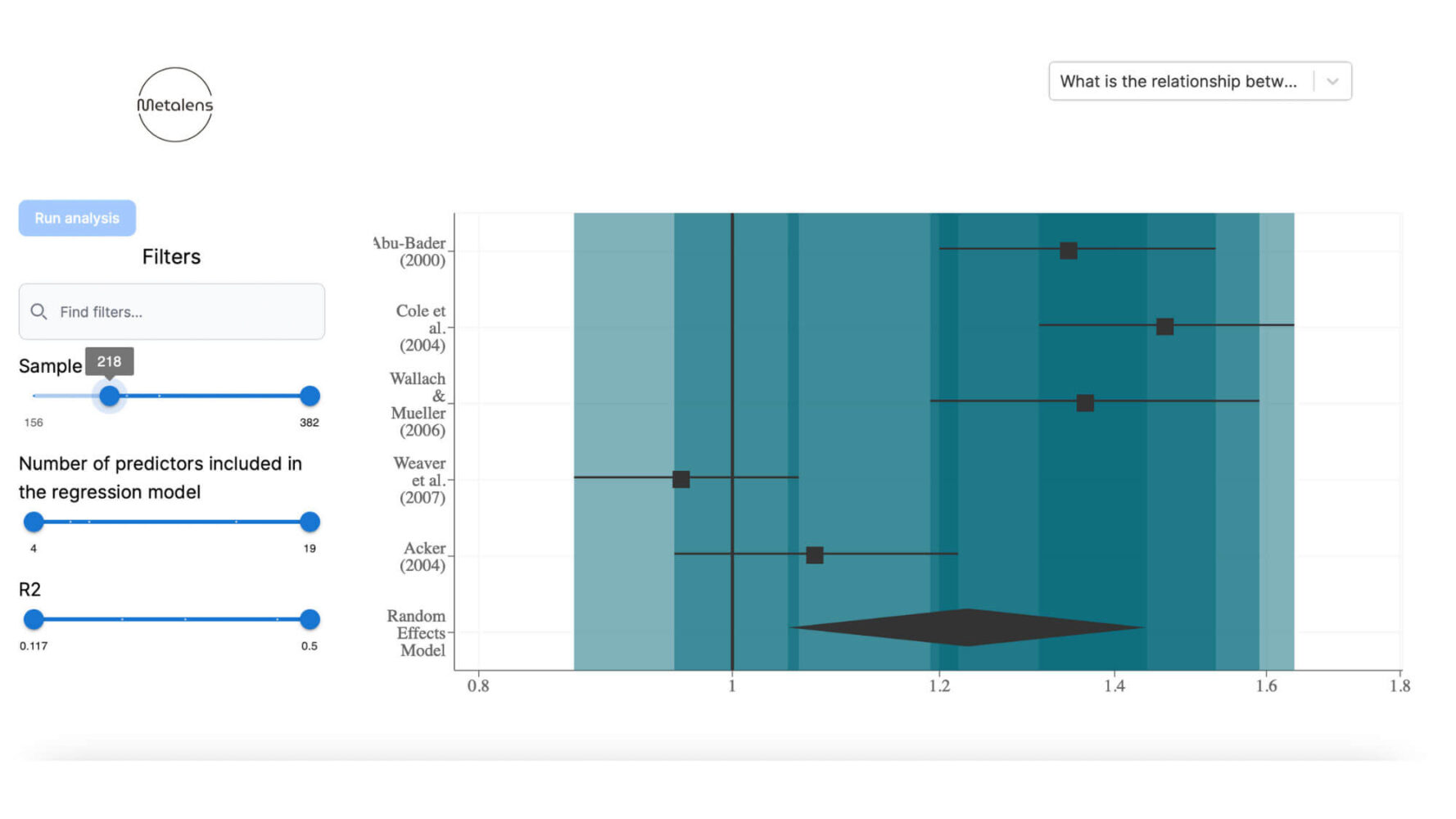

The project outcome is ‘Metalens’ – a small website prototype that allows users to interactively search and filter meta-studies.

It is publicly accessible at https://metalens.tech

Aggregating Scientific Results

Metastudies are statistical analyses that combine the results of multiple scientific studies on the same topic. This makes them a great starting point for collecting published research results on a specific subject. However, meta-analyses are usually not easily accessible to the general public: the relevant studies are often difficult to find or detailed subject-matter knowledge is needed to interpret the results. Further, their static, paper-based format makes it impossible to use the data to answer any questions not explicitly investigated by the researchers.

‘Living Reviews’ which are typically periodically updated reviews that are published online2, is a fairly new publishing format developed in response to this challenge. However, these are usually targeted at researchers and mostly focused on one specific point. Our project seeks to build a middle ground by creating a tool that provides insights into a broad range of topics to anyone interested in science, not just scientists.

Making it user-friendly

This requires two main challenges to be solved:

(1) To make the website accessible, the user interface needs to allow for intuitive interaction with the displayed scientific content.

(2) To make the website relevant, it needs to be based on an extensive database of scientific results of general interest.

In our project, we tried to investigate and prototype ways to address both of these challenges. Based on standard ways of displaying meta-analysis results in scientific literature, we built a website featuring an interactive visualisation of scientific findings with incorporated filtering functionality. Further, we have been iteratively developing a standardised yet flexible data storage format that enables us to easily add new studies to the website at any point in time.

Building a database

Regarding the actual building up of the database, we conducted research on already existing open-source databases and talked to academics doing research in meta-science3. Based on this, we decided to use the open-source metadat4 dataset as the foundation of our database of scientific studies. This allow us to first test the relevance of our service as well as its functionalities with potential users, before investing substantial amounts of time into data extraction.

Our next step in building a database is to use large language models (LLMs) for partially automated extraction of information from metastudies. We have started investigating state-of-the-art tools for retrieval augmented generation (ranging from ChatGPT to Llama2), and have achieved some promising results extracting text from individualised data samples. Yet it is exactly the scaling up of this process along with corresponding improvements in data extraction accuracy that we are setting our sights on right now. This would allow us to make our tool truly universal – and not just limited to a small set of scientific questions.

Link: https://tiny-boba-d30542.netlify.app/

Website: https://metalens.tech

Process Reflection

We started tackling our research question by getting an overview of alternative tools existing in the space. This led us to further refine our research question: while we had initially decided to – very broadly – digitise meta-analyses, we found that there was a lack of websites catering to the general public (as opposed to researchers). In response to this, we decided to focus on answering questions that are of general interest (e.g. What drugs help against the common cold?) and delivering information in a format that is understandable to people without domain knowledge. We understood that the first and most relevant step for our project was to find out whether we are able to build a product that people would actually be interested in using.

Figure 1: Screenshot from the prototype’s forest plot displaying aggregated study results fitting a set of criteria chosen by the user.

This is why we decided to initially focus on user experience development. In addition, by doing so we were able to fully draw on our respective interdisciplinary skill sets. While Johanna was able to bring in statistics knowledge and experience in data analysis, Linas contributed with his expertise in front-end development and insights from digital humanities. This resulted in a seamless task delegation with everyone taking over responsibility for a part of the project. Nonetheless, we both supported each other in the implementation phase which also enabled us to extend our respective skills and gain insights into the other one’s area of expertise.

Based on this experience, we would suggest that a new university should emphasise project-based learning. Retrospectively speaking, we drew a lot of motivation for learning from working on a ‘real’ product that we would both be excited to use. Further, the unexpected challenges that typically arise in any kind of real-world project naturally incentivized collaborative problem solving and transfer learning.

When it comes to technologies, we mainly investigated interactive user-interfaces. Our goal was to make it easy for anyone to use ours too. While we certainly have not reached the optimum with regard to user-friendliness, critically questioning and testing our design has already helped us improve the interface. Apart from this, we also investigated the use of language models for information retrieval. We ran small experiments with commercial APIs and locally hosted open-source models, thereby testing the feasibility of such an application. Initial results have been promising and we are aiming to explore this in much more depth in the future.