Urban Oasis

by

Sonia Litwin

Concept

When you walk through the city how do you feel? Are you connected to yourself? Or distracted, scattered, in a rush? Are you in control, or is the environment that controls you?

Urban Oasis lies at the intersection of environmental psychology, neuroaesthetics, and bio-inspired design. Grounded in the principles of architecture, neuroscience, and biophilia, it aims to create an artificial representation of nature that can be applied to the urban design of future spaces.

The phenomenon of the impact of the physical environment on human behavior, health, and well-being has long been the interest of researchers and designers alike. [1] The diversity of fields studying this relationship ranges from environmental psychology to embodied cognition, neuroscience, and architecture. Hybrid practices like neuroarchitecture try to bridge those disciplines to understand the correlation of architectural features with the brain basis of well-being. The studies published in top-tier journals investigate the significant relationships between certain characteristics of living spaces and their effects on human health including affective symptoms and cognitive abilities. The behavioral settings that encourage focus are shown to have a profound effect on human health. [2,3]

At the same time, distraction, in particular, is shown to have a decremental effect on health. Controversially it is the distraction and forced attention that are dominant feelings in modern urban spaces. [4]

If we view the places and the objects within them not as discrete, unrelated elements but as part of a larger order – a system of „wholeness.“, we can see that in this system certain geometric properties and structures have a universal ability to evoke specific emotional states. [1,5]

Wouldn’t it be then possible to use those visual qualities to engineer the feelings of focus into cityscapes? To create an Urban Oasis?

Biophilic hypothesis – „the urge to affiliate with other forms of life“ is a theory that suggests humans have an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life. This concept, now proven by research, is rooted in our biology and reflects a deep affiliation humans have with other life forms and nature as a whole. It suggests that “living structures“ possess qualities that evoke a natural and intrinsic response from humans. Natural environments are perceived as restorative and universally beautiful. [1,5,6]

However, there are places where “biological nature” cannot be invited. Places like hospitals, light-deprived small spaces, and space stations. Is it possible to use construction and design to recreate nature in those spaces? To create an “artificial nature”?

Urban Oasis explores the possibility of using the shapes and visual qualities of the forest to create a design language encouraging focus and calmness.

This project stands as a “preliminary exploration, a first word not a last word, an attempt to capture ideas and suggest how they might be developed and tested.” In this first chapter, I invite you to explore the visual qualities of the cityscape and their consequences for human health and well-being.

Process Reflection

We are constantly exposed to stimulation overload. “A man’s eyes cannot be as much occupied as they are in large cities by artificial things(…) without harmful effect, first on his mental and nervous system and ultimately on his entire constitutional organization” [7].

Most often, our perception of the environment is not sustained, but rather partial, fragmentary. Nearly every sense is in operation, and the image we experience is the composite of them all [6].

From all the senses, vision is widely considered to be the most important and most complex. The term ‚visual dominance‘ means that the sensual information is not treated equally. The

visual quality of the scenes seems to dominate over other modalities [8]. It is therefore reasonable to assume that our experience of the urban environment is to a great extent shaped by its aesthetics.

Many studies also support the fact that just by looking at ‚living structures‘ the patterns of brain activity transition to the states of restoration and healing“. However, little is known about which visual features of the natural environment have this restorative impact [9].

If we had this understanding. Would it be possible to create an artificial nature? To engineer an architectural language of harmonious shapes and structures that would evoke a state of calmness? To create an Oasis in urban space?

But how to understand how we perceive the forest?

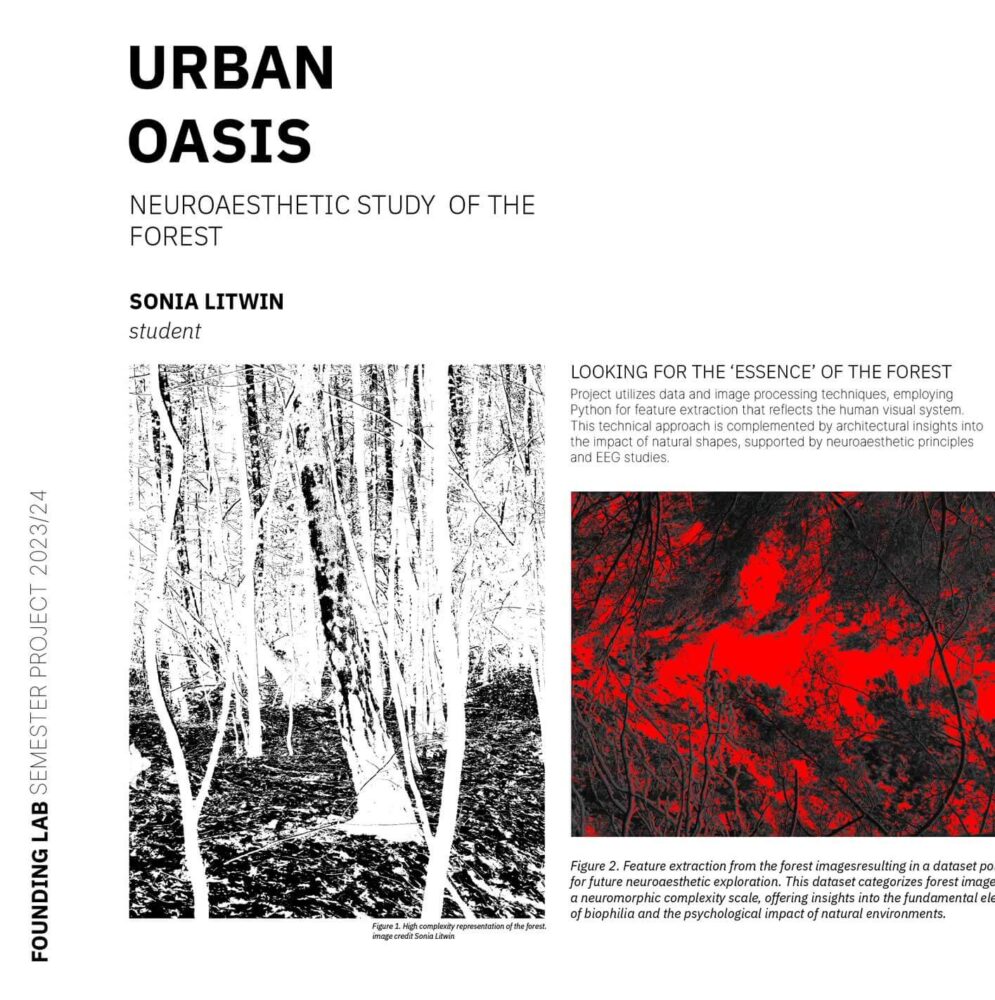

Visual perception has long been a fascination of the researchers. Cognitive science and neuroaesthetics agree that there are two main processes, top-down and bottom-up, in which the human brain formulates the images of objects. Moreover, the human visual system is wired to organize the visual input in terms of image features: edges, shapes, and structures. The bottom- up visual pathway starts at the lowest level of the image – edges. From there subsequent regions of the visual cortex ‚build up‘ the image constructing the shapes and structures. The images we see can be, therefore, understood in terms of the basic features.

But how do we measure the actual information content of the image? The image complexity?

For this purpose a commonly used measure is entropy. It has been also shown that the complexity of the image is related to the emotional valence [10].

To understand how the image of the forest is perceived in the visual cortex and how it impacts the emotional states I’ve used a set of tools that mimic the human visual processing pathway.

The resulting dataset represents the images segmented into the features and organized on the scale of decreasing complexity. Original photographs are the representation of the highest level of complexity – textures.

The aim of segmenting images into different complexity levels is to study, with the use of an EEG headband, the brain response to the obtained geometries and determine the minimal level of complexity that has the potential to create the well-being enhancing effects, as measured by the front alpha asymmetry, similar to the experience of forest viewing. This would enable the answer to a question:

Is it possible to use shapes and structures of the forest to create an architectural language of ‚artificial nature‘ that evokes the same brain response as the ‚real nature‘?

In this study, the images of the forest are viewed as artificial agents and the relationship between them, and human beings is studied with the approach derived from human-machine interaction. This way the artificial nature becomes an agent that is a part of the larger system of behavioral setting – the speculative urban space of the future.

Contributors:

Discovery process: Campbell Orme, Product Design Lead for XR, Meta Reality Labs

Research

Neuroscience methods: Angela Vujic, Ph.D. Researcher at Fluid Interfaces Group in MIT Media Lab

References

[1] Alexander, C. (2004). The phenomenon of life: The nature of order, book 1: An essay of the art of building and the nature of the universe. Center for Environmental Structure.

[2] Xu J, Liu N, Polemiti E, Garcia-Mondragon L, Tang J, Liu X, Lett T, Yu L, Nöthen MM, Feng J, Yu C, Marquand A, Schumann G; the environMENTAL Consortium. Effects of urban living environments on mental health in adults. Nat Med. 2023 Jun;29(6):1456-1467. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02365-w. Epub 2023 Jun 15. PMID: 37322117; PMCID: PMC10287556.

[3] Azzazy, S., Ghaffarianhoseini, A., GhaffarianHoseini, A., Naismith, N., and Doborjeh, Z. (2021). A critical review on the impact of built environment on users’ measured brain activity. Archit. Sci. Rev. 64, 319–335. doi: 10.1080/00038628.2020.1749980

[4] White, H., & Shah, P. (2019). Attention in Urban and Natural Environments. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 92, 115 – 120.

[5] Wilson, E.O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[6] Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. MIT Press.

[7] Beveridge C.E., Rocheleau P. Frederick Law Olmsted. Rizzoli International Publications; New York, NY, USA: 1995

[8] Hutmacher F. (2019). Why Is There So Much More Research on Vision Than on Any Other Sensory Modality?. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02246

[9] Olszewska-Guizzo, A., Sia, A., Fogel, A., & Ho, R. (2020). Can Exposure to Certain Urban Green Spaces Trigger Frontal Alpha Asymmetry in the Brain?-Preliminary Findings from a Passive Task EEG Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(2), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020394

[10] Elizabeth Y Zhou, Claudia Damiano, John Wilder, Dirk B Walther; Measuring complexity of images using Multiscale Entropy. Journal of Vision 2019;19(10):96a. https://doi.org/10.1167/19.10.96a.