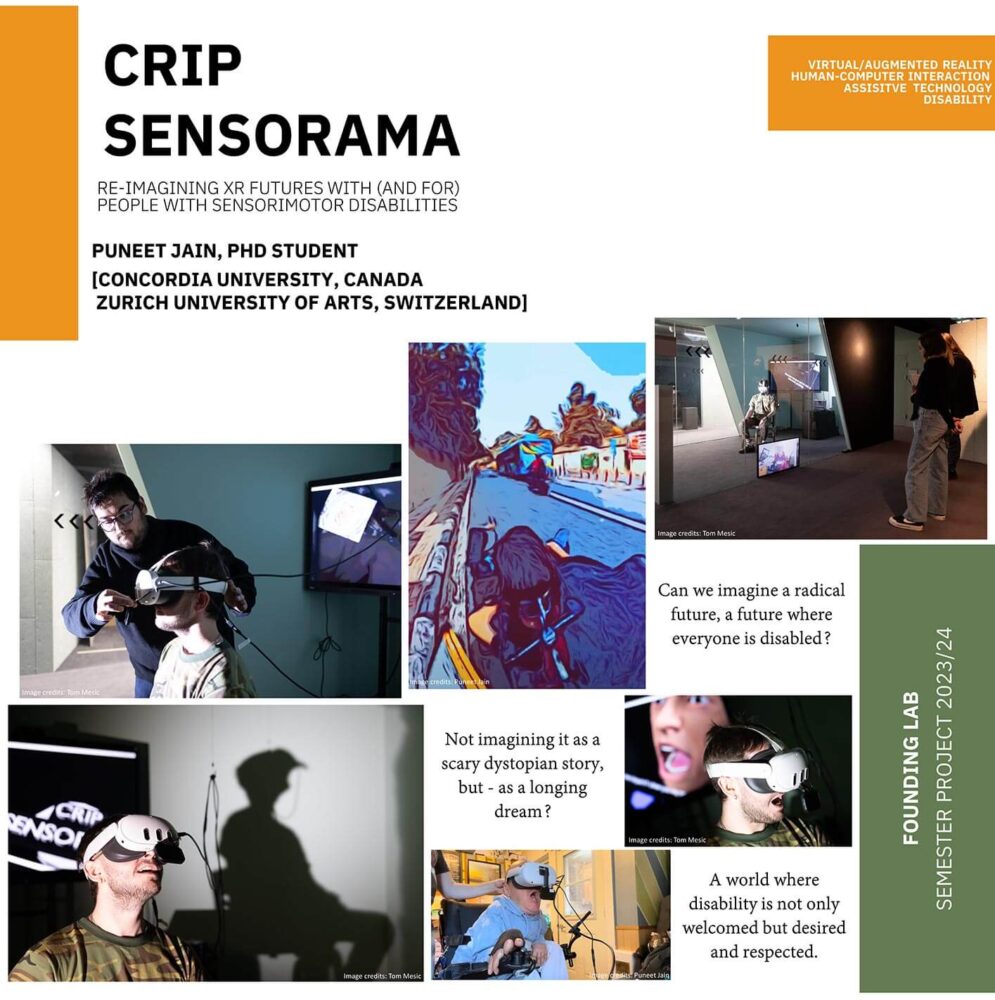

Crip Sensorama

by

Puneet Jain

Concept

As a part of the FOUNDING LAB program, I investigated how the technologies of XR (eXtended Reality) could be re-imagined and hacked (in their early stages) to act as a platform of storytelling for (and with) people with disabilities – enabling people with disabilities to shape and share their own future imaginaries. XR is an umbrella term for computer-generated environments (Virtual/Augmented Reality (VR/AR)), comprising a set of body-worn interfaces (head-mounted displays, hand-held controllers, wearable haptics etc.) that bridge the physical body within a continuum of real and virtual space. However, the current generation of XR technologies demand an intricate coordination between the head (e.g. 360-degree head movements) and dexterity of hands (e.g. rapid finger movements on hand-held controllers) to navigate and interact inside the virtual environments – a gestural landscape that my close friends and collaborators Eric Desrosiers and Chrisitan Bayerlein cannot afford.

Eric (who is based in Montreal, Canada) and Christian (who is based in Koblenz, Germany) are artists and disability activists living with quadriplegia and regularly work with technologies such as robotic arms for painting, facial recognition algorithms for music generation, and brain-controlled interfaces for flying drones. Even with such a technological expertise, unfortunately, they cannot access the world of Virtual and Augmented reality – revealing that these technologies are still designed with implicit assumptions about human bodies, what HCI researchers Gerling and Spiel have also described as a “corporeal standard” (2021) (i.e. an ideal white able-bodied user).

Through my project, ‘Crip Sensorama’, I open the world of VR/AR for Eric and Christian by enabling them to access VR/AR through a sequence of mouth gestures. Using the methodology of ‘criptastic hacking’ (Yergeau, 2014) (an approach where technologies are hacked along with people with disabilities), I trained and parametrized a set of mouth gestures (e.g. opening of the mouth) using machine learning algorithms on Eric and Christian – acting as an input method to navigate and interact in VR and AR. Additionally, utilizing the immersive medium of VR/AR storytelling, 360 degree videos, spatialized sound, I stage Crip Sensorama as invitation for people with and without disabilities to re-configure and re-adjust their facial micro-gestures to that of Eric and Christian – the tongue, the chin, the gaps between the upper and lower lip, opening of the mouth as a story unfolds around disability culture and living. Hence, enabling the audience to adjust to the temporal experience of living with disability, what disability scholars have described as living in ‘crip time’ (Kuppers, 2014; Samuels, 2017) foreseen as “a means to wrestle the ways in which “the future” has been deployed in the service of compulsory able-bodiedness” (Kafer, 2013).

Overall, Crip Sensorama as a VR/AR project harnesses the technologies of VR/AR and artificial intelligence to critique the perception of disability as a “problem” but rather flips the power dynamics by introducing the non-disabled groups to disability culture and living through accessible VR/AR technologies.

Process Reflection

Crip Sensorama, as a project investigates how the current generation of Virtual and Augmented reality technologies are designed with implicit assumptions about human body-minds. Demanding extensive bodily movements such as rapid hand gestures and hand-held controllers as the only input modalities to navigate, move, and interact, 360-degree head movements as measures of immersion – reveal that the proposed “Metaverse” is inaccessible for people living with sensorimotor disabilities such as my friends and collaborators Eric Desrosiers and Chrisitan Bayerlein who have quadriplegia. This does not come as a surprise as accessibility is often an afterthought, a bare-minimum action performed by able-bodied people to “adjust” the marginalized body-minds, what disability media studies scholar Elizabeth Ellcessor has described as the ‘common-sense idea of accessibility’ (2017). Crip Sensorama as a project thus critiques such an ableist design strategy and instead draws on “Nothing about us, without us” (Spiel et al., 2020) that calls for including people with disabilities in the design and critical modification of technologies from the very start of design process.

Hence, as a non-disabled HCI researcher and artist, I worked closely with Christian and Eric (who have quadriplegia) to investigate how technologies of VR/AR could be hacked, tinkered, and modified to make them accessible for people with sensorimotor disabilities and in-return how accessible VR/AR (as a storytelling medium) can enable us to reimagine bodily subjectivity, interaction, and experience. Concretely, I followed the methodology of ‘criptastic hacking’ (Yergeau, 2014), an approach where technologies are hacked and reversed by embracing the already existing resources, bodily knowledge, and “disabled” technologies (technologies already in use by people with disabilities). Hence, with Christian’s and Eric’s long practice of using mouth gestures to operate and control computer joysticks and their wheelchairs, I developed custom mouth gesture recognition algorithms, and a set of mouth gestures as means of input to navigate and interact in VR/AR.

Additionally, utilizing the immersive medium of VR/AR storytelling, 360-degree videos, spatialized sound, I stage my project ‘Crip Sensorama’ as a multisensory 10–15-minute VR/AR installation. Acting as an invitation for people with and without disabilities to re-configure and re-adjust their facial micro-gestures to that of Eric and Christian – the tongue, the chin, the gaps between the upper and lower lip, opening of the mouth as a story unfolds around disability culture and living.

Working as a non-disabled researcher/artist with people living with quadriplegia during the FOUNDING LAB summer school, I got exposed to the hacks, the wisdom, and unique bodily embodiment of navigating an inaccessible world – an everyday experience for Christian and Eric. Hence, thinking of the university of the future, I would like to encourage the new university to not only welcome people with disabilities but also embrace the knowledge they bring in (for instance, as starting points: incorporating disability studies, introducing students to sign languages (ASL, ISL) and mathematical tools used by people with low vision and visual impairment such as Taylor Frames).